Dropping Mics

I used to love arguing about politics on the internet. I do that less now, but over the years, my willingness to throw down has brought me to an understanding –

No one wants to actually be right about anything.

People just want to feel right about something. And, more importantly, they just want to appear to be right to other people.

The truth is that we’re just fine being wrong. So long as we can plausibly tell ourselves that we’re right, and other people perceive us as being right, then whether we’re actually right about an issue doesn’t matter in the slightest.

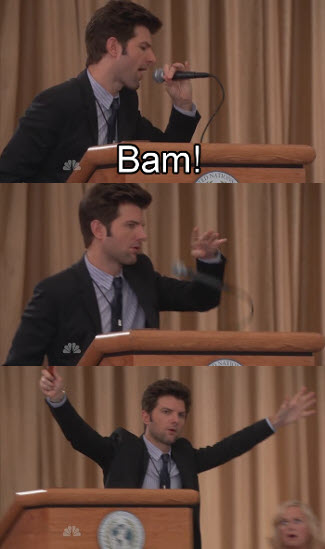

What we really want is a dopamine hit. We want that “mic drop” moment, where we bust a rhyme so dope that we drop the microphone and walk off the stage, and our opponent is rendered speechless and can’t even mount a response.

For example, the phrase “owning the libs” has become a description of what conservatives seek to do (“owning” is a term from the video gaming world, which vaguely means “humiliate and destroy”). Instead of denying this, an editor for The American Conservative conceded it and celebrated it.

“Owning the libs” is a way of asserting dignity. “The libs,” as currently constituted, spend a lot of time denigrating and devaluing the dignity of Middle America and conservatives, so fighting back against that is healthy self-assertion; any self-respecting human being would…Stunts, TikTok videos, they energize people, that’s what they’re intended to do.

(The same is undoubtedly true in liberal circles, though, for whatever reason, they don’t seem to have a catchy phrase for it.)

I watched a video the other day that laid out an argument about a sensitive social issue. I thought it was a compelling video – it summed up my personal feelings and it gave me a lovely dopamine hit because it made me feel secure in my rightness.

Feeling the strength of this rightness, I sent the video to a friend, with whom I’ve had debates about social issues in the past, and who I knew was on the other side of the issue. I framed it as “this is why I’m not wrong.”

My friend – who I respect greatly – had seen the video and responded with a rebuttal from a third-party. I read through that rebuttal and got anxious. I didn’t like the rebuttal because I had been secure in my rightness, and the rebuttal threatened that security.

So, I immediately set about finding a counter-rebuttal. I was sure one existed, because the internet can be a small place, and I’m sure the authors of the original video had seen the rebuttal and have no-doubt prepared responses to it.

But then I stopped – I thought, what was the point? I could find counter evidence and send it to my friend, but there’s no chance he would just accept it and say, “Huh. I guess I was wrong. Nice job.” I sure didn’t do that when he sent me his response. My friend would, of course, just go find a counter-counter rebuttal, and we’d be off to the races.

(Yes, yes – I never should have sent the video in the first place. I get that.)

I think anyone can form an effective rebuttal to about anything, especially when it comes to complicated issues. When arguing with someone, we look for “mic drop moments” where we can throw an indisputable argument on the table that leaves our opponent speechless.

This is why political arguments are fundamentally unwinnable. The internet has given us so much content and so many talking heads that will agree with any viewpoint, that every political argument eventually devolves into “evidence trading.”

I once debated politics with someone for almost two years. It was almost exclusively just us trading evidence about which side was worse. There was no depth, no analysis – our minds were made up. We didn’t care if we were actually right about anything. We just wanted to feel like it.

But it’s so hard these days to be unambiguously right about anything. The world exists in overlapping shades of gray.

I’ve written before about how the US economy is so complicated that it probably defies any causal analysis in the short term. Lots of issues are exactly like this. A skilled and well-researched debater on almost any issue can dig into enough cracks to spin evidence in such a way to support any position. You just have to creatively frame the original complaint until you can find evidence to support it.

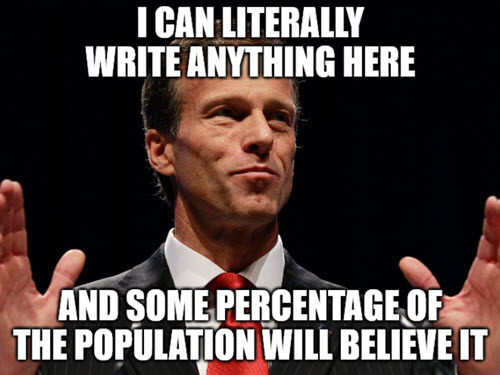

Inevitably, someone will take some “evidence” – in total isolation of all other factors – and make a meme out of it. Then we mic drop it on Facebook as if this is the sum total of all possible arguments, factors, and nuances into the issue.

There is apparently no issue that can’t be explained by a picture with writing on it (the key: use the “Impact” font, white with a subtle black outline).

Newsflash: any public figure can look bad in an isolated moment. I hate (hate) to use the phrase “out of context” because it’s used way too often to excuse legitimately bad behavior. But it fits – you can find any public figure, no matter how “good” overall, and find some moment where they look like complete trash, then isolate that moment and stick it in a meme.

Who cares if the other 99.9% of that person’s behavior is in complete opposition to the single moment or quote you captured in your meme?

You still won! You got dat sweet dopamine hit, bro! Yay!

Highly related: if there’s no defense, then we just fall back to the default: “Your Side Is Just As Bad And Here Is An Example Of That.” In the end, it doesn’t matter what our side does, as long as the other side is Just As Bad™.

And here’s something else we do, deftly –

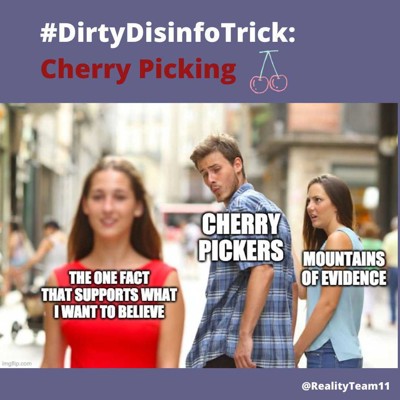

When we find an argument that reinforces what we wanted to believe in the first place, we venerate it as The One True Evidence…and we stop looking.

And that’s the key – if we find evidence that disproves our belief, we keep searching because we know there’s a mic drop out there somewhere. When we do find the evidence that agrees with our position or values, we hug it close, pat ourselves on the back for being so well-informed, and then luxuriate in the security of our rightness.

Here’s a 14-second video. This woman is all of us.

(I don’t know how you feel about vaccines, and it doesn’t matter. That’s not the point. Substitute anything you want for that issue.)

This goes by a couple names:

- Confirmation Bias says that we’ll be drawn to evidence that supports the position we wanted to hold in the first place, and we’ll discount evidence that threatens it.

- Survivor Bias says that history is written by the victors, and oftentimes the only reason someone has evidence for a position is because that evidence “won” the battle for their mind, and they stopped looking when they found it.

One thing you find common in intelligence agencies like the CIA is the existence of “red teams.”

A red team is a group that helps organizations to improve themselves by providing opposition to the point of view of the organization that they are helping. They are often effective in helping organizations overcome cultural bias and broaden their problem-solving capabilities.

If an agency wants to make sure their thinking is correct about something, they form a red team whose job it is to argue the point from the other side. They play Devil’s Advocate and try to poke holes in the way the organization is leaning.

Bill Gates used to the do the same thing. He would start meetings by asking for the bad news – he wanted to know all the things that were wrong with something. (I just finished his book from 1999 in which he actually has a chapter entitled “Bad News Must Travel Fast.”)

We never do this as individuals. We want to be able to tell ourselves that we’re right, and we want to be able to plausibly deny any evidence to the contrary. If someone rebuts us, we just need a handy counter-rebuttal, and we’re good.

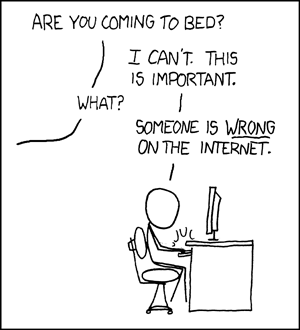

I saw a cartoon the other day that went like this:

Man #1: “Give me a source for your claim!”

Man #2: “Here is the source, right here.”

Man #1: “I don’t want a source! I just want you to be wrong!”

(It was somewhere at Poorly Drawn Lines, but I don’t have the specific link.)

The scientific method would say that we should gather evidence, evaluate it, and work forward to a conclusion. But, in reality, we already know our conclusion, and we just work backwards to find the evidence to support that. Evidence that works against us, we disregard or seek to rebut; evidence that supports us, we relentlessly promote.

Imagine if a coach asked the referee: “Can you just extend regulation time until we have more points than the other team?”

We are that coach.

No one is wrong anymore. We just don’t yet have all the evidence to plausibly deny it.

But just give us a little more time, and by God we’ll find it, because that mic isn’t gonna drop itself.