CMS Implementations Deck

Section: Sales (44 slides)

- The images will load as you scroll to them. If you scroll too fast, you might get ahead of the loading.

- The permalink goes to the single page for a slide with “Prev” and “Next” links. It's suitable for bookmarking or sharing.

I spent a decade selling CMS software and services. I wrote an entire book about my experiences doing this.

Things You Should Know: 25 Lessons I’ve Learned About Selecting Content Technology and Services

Put another way:

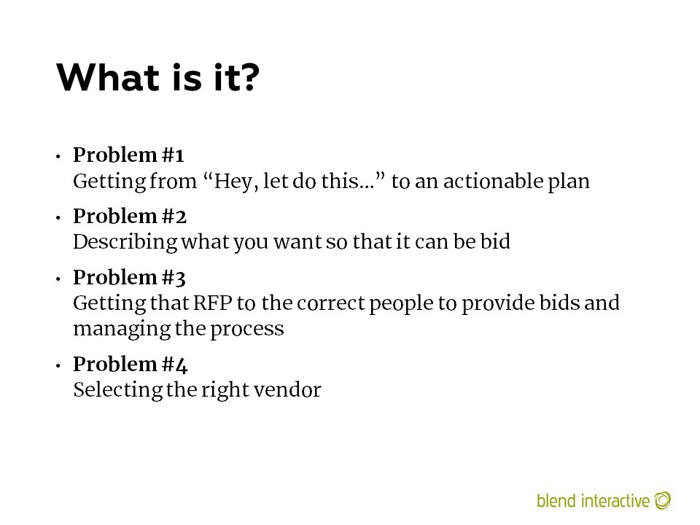

- Deciding what you want

- Describing what you want

- Managing a selection process

- Making a good decision

On this slide I say “…the right vendor,” and I regret this because it makes it seem like there’s one right choice. In reality, there might be a lot of vendors that work for you. Some may work better than others, but you shouldn’t be paranoid about your choice. What’s more important is what happens after the choice – how the software is implemented, and how you manage the vendor relationship.

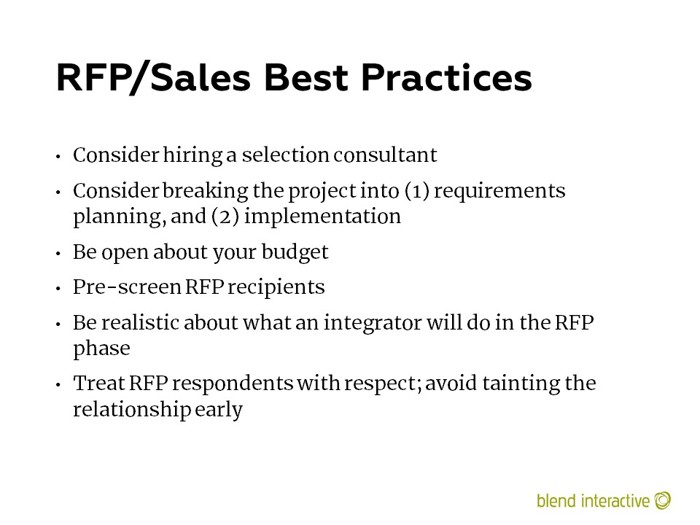

You can hire people to help you go from “We need a new website!” to an RFP that can be effectively bid. These people are called “selection consultants.” (I list some firms later on.)

You’ll “pay for it” in advance, by hiring someone. Or you’ll “pay for it” later, when your mistakes cost you more than better planning would have.

If you had a really vague idea, I would quote you a consulting engagement to help you refine it. If you didn’t want to do that, then I would simply wish you success with your project.

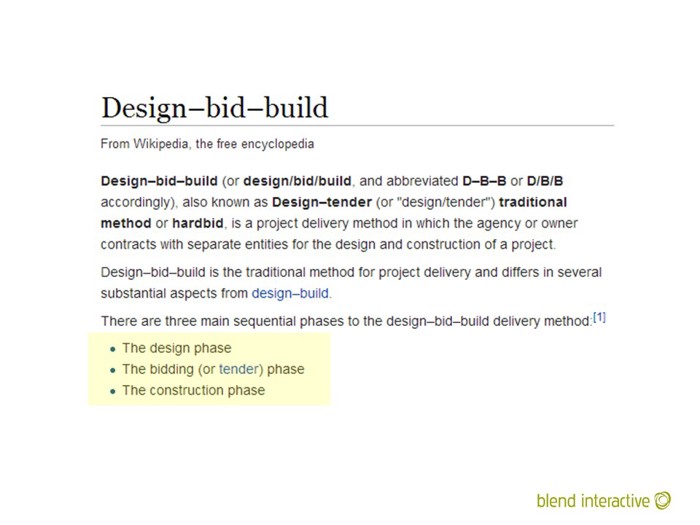

The Design-Bid-Build model is common in the construction industry. An explicit fee for an architect is expected. No one starts building an office building without a blueprint they paid for.

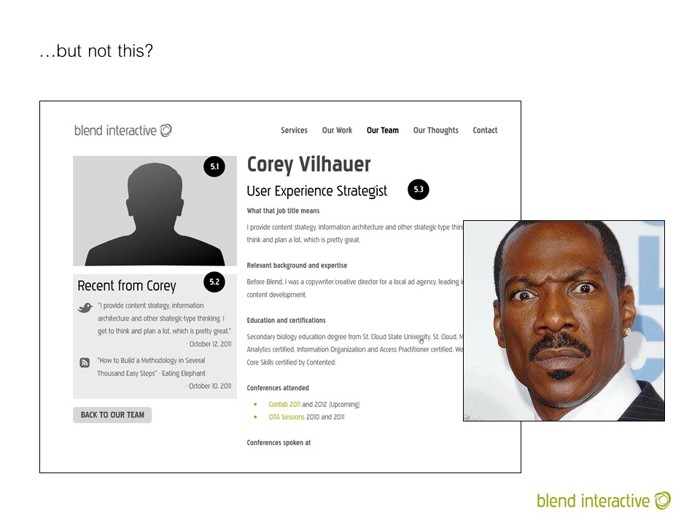

People expect to pay an architect to design a house. (Eddie is happy.)

(I have no memory why I decided to use Eddie Murphy as an example here. Maybe because he has great facial expressions?)

For some reason, people get annoyed at paying a content strategist to plan a website. (Eddie is angry.)

This has changed quite a bit since 2014. It’s much more expected to pay for design/plannings services now, but it used to be an uphill battle.

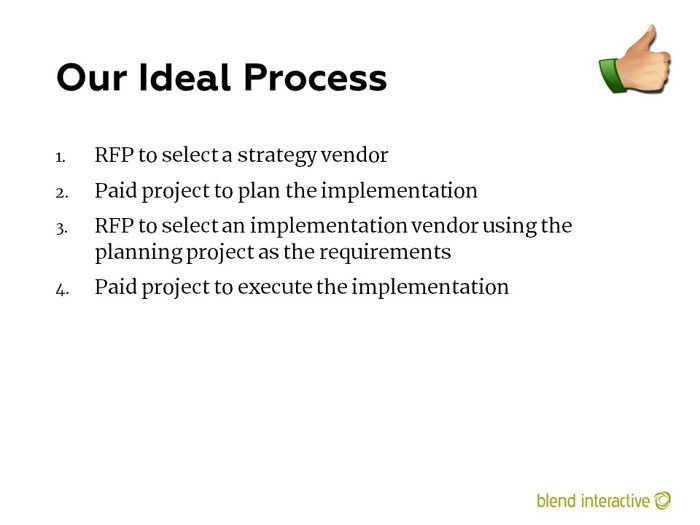

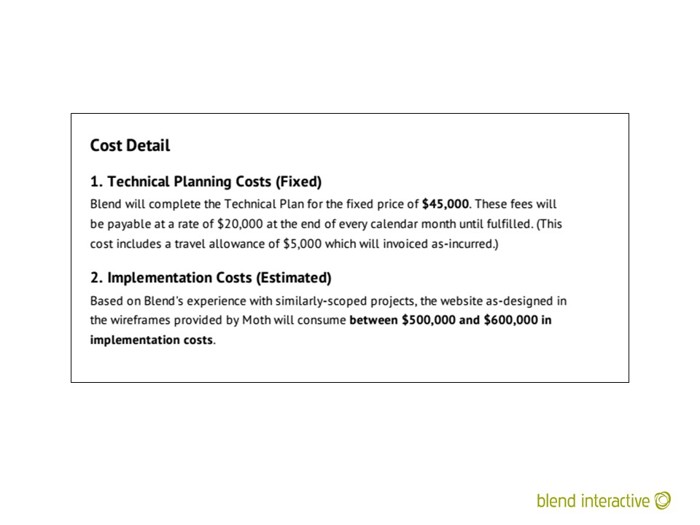

This is how Blend would bid projects. We’d charge a fixed amount for the plan, then we’d estimate a range for the implementation.

I firmly maintain this is the only honest way to approach these things.

A worse option is if they don’t pad, and they start losing money on you. Buying services isn’t like buying a used car. You do not want to be “the unprofitable client.”

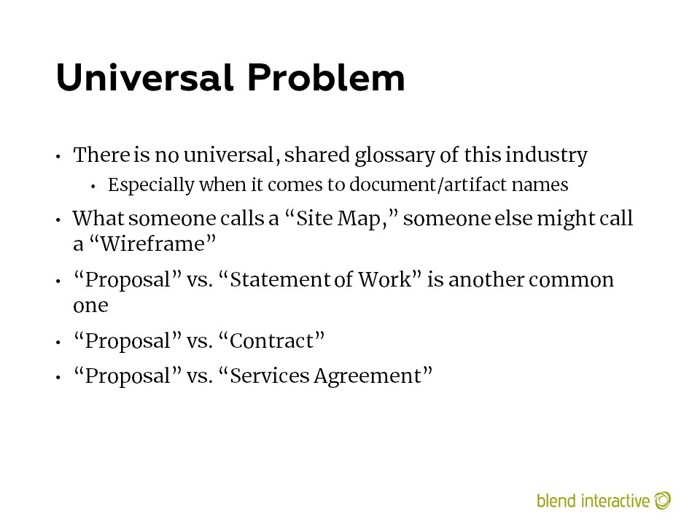

There are lots of different design artifacts you might get. None of these names are standardized. What someone calls one thing, someone else might have a totally different name for.

This is a great book on how to codify a design. The title is telling: you need to “communicate” (verb) your design. You know what you want, you just have a figure out a way to get other people to know it too.

Communicating Design: Developing Web Site Documentation for Design and Planning

Cattle calls – where they blindly send an RFP to dozens of firms – were the worst. We would very rarely respond to these.

Also, it’s worth mentioning that many firms won’t respond to RFPs at all. There’s a whole book about this: The Win Without Pitching Manifesto

“Vibe” matters. The personality of your organization will come out in your RFP and how you manage the sales process. There were times we bailed out of a process just because the client gave us a bad feeling.

Sometimes we felt like they’d be abusive to work for. But more often, we just thought they had wildly unrealistic expectations and had no idea what they were getting into. We’d try to talk to them and instill some realism, but that mostly didn’t work. I don’t mean to put Blend on too much of a pedestal, but we were unrelentingly honest, and other firms often…weren’t. Every time we were trying to educate an organization and move them to a realistic view of their project, 10 other firms were just telling then exactly what they wanted to hear.

Often, I would review an RFP and think to myself, “This is going to be won by whichever firm is willing to lie the most.”

Most RFP responses will be an intersection of software vendor and services firm. You need to know where those lines are drawn.

RFPs can get abusive in this respect. Don’t ask me to plan out your entire project for you just to try and win the business. There’s a blurry line between understanding how someone would manage a project and manipulating them for free labor.

I wrote about this a bit in The Quandary of the Web Development Sales Process.

Spec work = speculative work. Work you do at no fee to try and win a project.

There is actually a campaign to persuade service providers to refuse to perform spec work. People who do work on spec really damage the industry for everyone else.

I wrote about this quite a bit in Just Give Us a Budget Target.

Paragraphs like this don’t help, because I still have no idea if we’re in the same ballpark. You saying you have “experience” and are “realistic” might mean something totally different to me. This paragraph was from an RFP that I declined to bid because I didn’t know how much money they had, and I suspected they didn’t have enough.

I wrote about this specific RFP in The Peril of Not Stating Your Budget Upfront.

Responding to an RFP is a gamble for the integrator. They need to weigh the odds. In some respects, you need to sell your project to them. If you don’t, then the only integrators will respond are the desperate ones, which are the exact ones you don’t want.

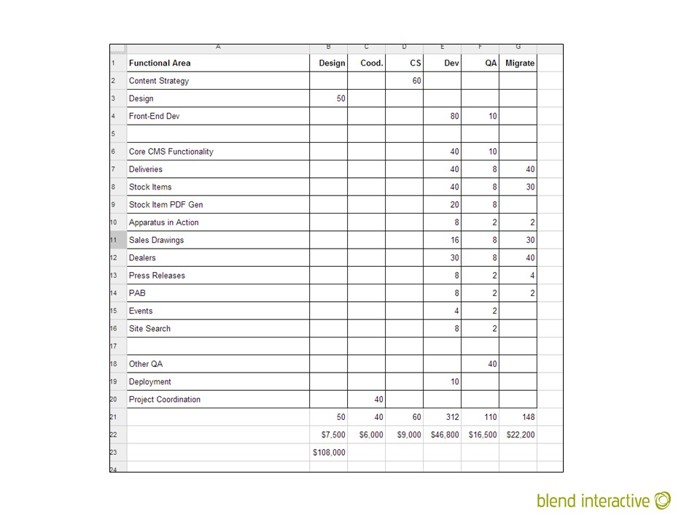

An example of how Blend bid projects in 2015. The rows are tasks, and the columns are resources.

This has changed a bit at Blend, I understand. They’ve moved to a process where they provide an overall estimate, then do specific bids on tasks as they move through the project.

Just understand that this stuff is hard. Bidding services work for something as complicated and intricate as CMS implementations is notoriously difficult. I wrote about this in a post that’s been very popular over years: Everyone Wants a Number.

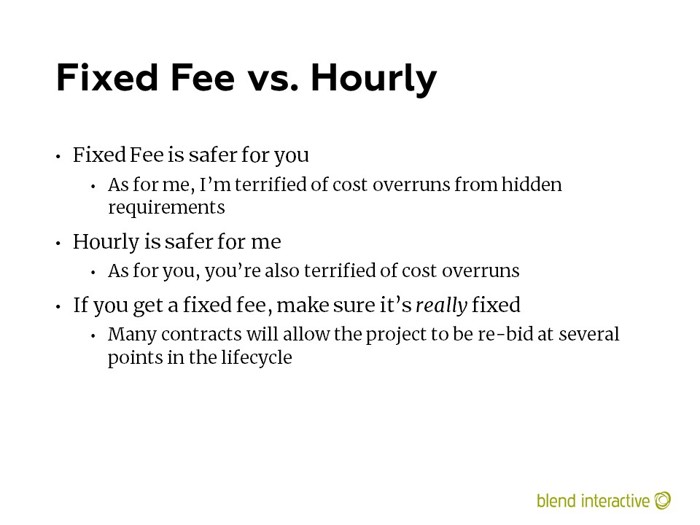

Pricing and negotiation is fundamentally about managing and assigning risk. Both sides want the least risky arrangement they can negotiate.

Regarding the last point – lots of numbers are “fixed” until something goes wrong. Then it just becomes an argument about the requirements and whether or not they were met.

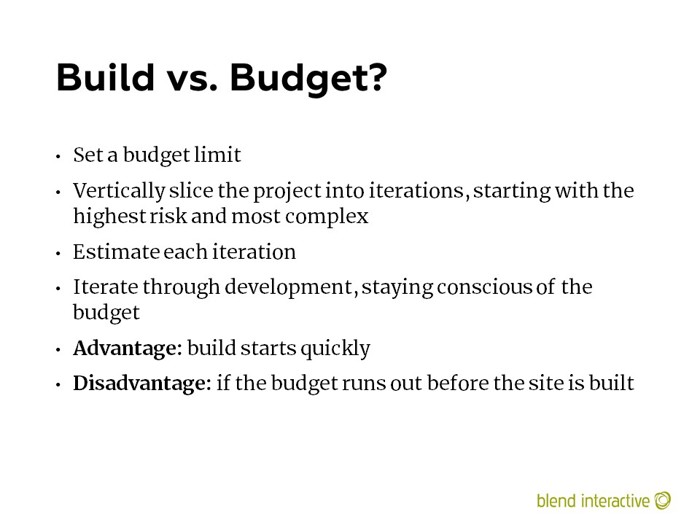

This slide came from a guy who attended my first workshop in Philly. He was with a Kentico integrator out of the U.K. and he swore this model worked well for them.

I included here as a perspective from someone else, but Blend has actually moved in this direction for projects: a good faith estimate, then more specific bids on tasks as they come around.

In retrospect, not “both” – if they’re padding, then they’re not stupid, they’re smart and pragmatic.

If an integrator is being pushed on this, the best answer is to bail out. The next best answer is to just keep padding the bid until you can sleep at night.

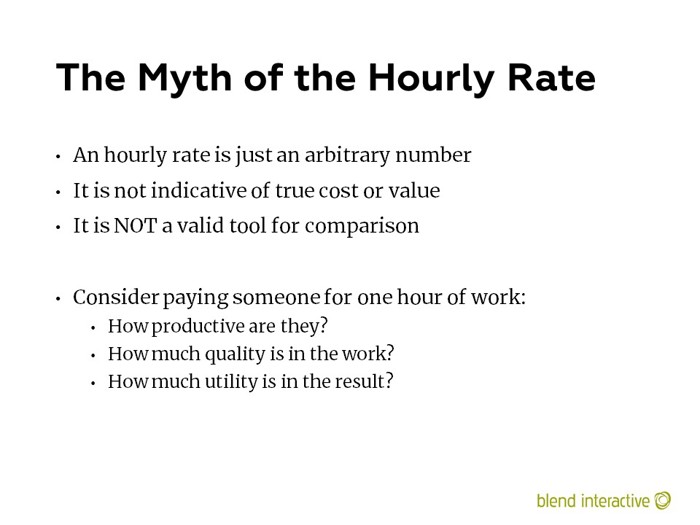

This mostly came from a post I wrote, unsurprisingly also called The Myth of the Hourly Rate.

As I noted earlier, these people are generally called “selection consultants.” They usually do this alongside other, more broad-based technology consulting. I don’t know of any people who do only selection consulting and nothing else.

Some consulting firms that will help you select integrators and write RFPs.

- J. Boye is now Boye and Company. The first time I gave this session was at their conference.

- Digital Clarity Group fragmented a bit. Several people went off and started The Content Advisory. And DGC itself is very concentrated around VOCalis now, which is a particular product.

- Real Story Group still does this, in the context of larger content technology advisory

And, of course, you might already have a subscription with Gartner or Forrester or Aberdeen or any number of other firms that do technology advisory.

If I get called in by a selection consultant, and I fall flat on my face, they won’t ask me to come pitch again, and that’s not good for me. So, I’m incentivized to do good work.

Additionally, selection consultants know how much we charge. They’ll vet you for budget before they call us in, because they don’t want to get a bad reputation for hosting wild goose chases.

Because of this, a selection consultant-led sales process would have my absolute and full attention.

I sent someone a proposal once. They responded, “Looks good. I just need a Statement of Work.” So, I changed the title on the document to “Statement of Work” and sent it back to them. They duly signed it.

What is not included is incredibly important, because people will mentally extrapolate a document to cover what they think it should cover. We would include a section called “Assumptions,” which basically stated all the things we believed to be true about a project, and all the things we wanted to be clear we weren’t doing.

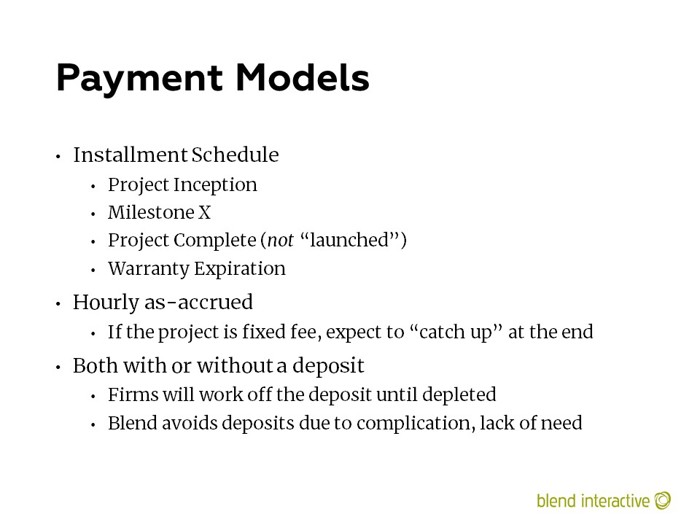

Integrators need predictable revenue. They need to know when they’re getting paid.

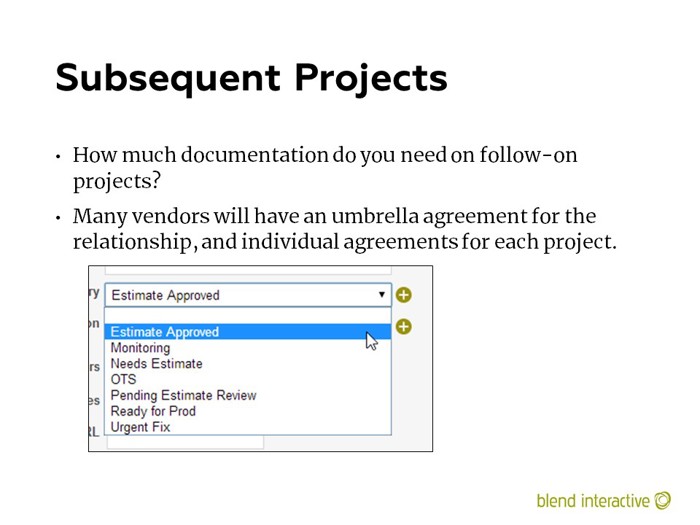

The “two agreement” approach is common. Blend had a one-time “General Services Agreement” that would govern the relationship. When a specific project needed to be bid, we’d do a “proposal” or “statement of work” for that project.

But not every follow-on project needs to be bid. Often, customers would purchase a block of hours every month, and we’d just work with them to divide that up between projects and tasks in their backlog.

The graphic is an example of how many follow-on projects get estimated – via work tickets. A ticket will be opened by the customer, the integrator will put some “Estimated Hours” in the system, and the customer will approve the work order.

These projects don’t really rate a full proposal, and you hopefully enter into a good working relationship with your integrator so that informality like this is not a problem.

If someone is jerk during sales, they’ll probably be worse during the project. The sales process is a “first date” that lets you measure how much you’re going to like working with someone.