How Should a CMS Repository Understand the Content Within It?

Last week, I wrote about how CMS repositories would need to adapt to the coming changes around AI.

I said this:

My belief is that the CMS of the future will be a set of strict rules around a content model, and that will be “beyond the reach” of AI. AI engines can do whatever they want with content, so long as they obey the model rules we put in place…

And, more succinctly:

A good content repository in the age of AI should be well-defended and well-described.

I decided to play around this with a little bit.

I wanted to create a “CMS repository” that was “well-defended and well-described.” I was wondering if I built out a repository in such a way that it would ensure good data and would be able to describe itself to AI agents, how would that affect my ability to apply AI-generated process agents to it?

Put another way: if we have a great repository, will we get better results from vibe-coding? Could the repository itself serve as an integral part of the vibe-coding process? Could I be “repository-centric,” and let AI handle all of the other work?

So, what repository system did I pick for this experiment?

Now, you can argue that choice, but here was my reasoning:

- It’s super easy to work with

- SQL databases are, by definition, self-describing; every one of them will serialize the “content model” to a text file of SQL DDL

- There’s effectively no “space” between the data storage and the SQL API, but I’ll talk more about this below…

My goal was to lock down a database/repository as securely as I could, both to ensure no bad data could get in, but also because a well-defended repository is well-described by definition.

I came up with idea of a simple “Friend CRM” – a database to track my friend’s information and allow me to store notes I take about them.

It was pretty simple:

- A User was a person who could work with the data (more on this below as well…)

- A Person record contained information about a person

- A Note record contained some textual notes about something

- A Note could be associated with one or more Person records

- Both Person and Note records could have Tags

- Every time a Person or Note was inserted, edited, or deleted, a record indicating this would be written to a history table, along with a serialized version of the old data (if applicable)

Very simple. But what I tried to do was codify all the business rules in the database itself, instead of enforcing them at the application or UI layers.

In general, developers tend to push validation off to the application layer. Our core data storage tends to be “loose,” and we just filter and strain the data before we try to persist it. Our general practice is we won’t attempt a database operation unless we already know the data is good.

This is fine, but it leaves a “gap” between the data storage and the content/data model. Our repository will store far bigger data variances than we intend. The theoretical problem is that something could conceivably get “under” the app layer.

This isn’t likely, but imagine if someone got SQL access to your database – this usually gives developers chills. “Use the API!” they scream. Anything going directly to the repo is considered potential bad data, because the API is the “sheriff.”

flowchart LR

A("Repo")

B("API

(the only proper gateway)")

C("Good Incoming Data")

D("Bad Actor

(sneaking in the back door)")

C-->B-->A

D-->A

This is pretty normal in modern web apps, but the API becomes effectively where the content model is defined, because that’s the finest “strainer” for the data. If the API is the last word on the type of data than can be persisted, then the core repository system and the API are effectively a bundle that have to be used together.

In this case, I was trying to define the database in such an exacting way that it became self-describing and self-defending. The database would both store the data and understand the model intuitively.

My litmus test was, “Could I give someone SQL-level access to this database without fear?”

To this end, I spent a lot of time learning about SQLite CHECK constraints. A simple “constraint” is a general rule, like “NOT NULL.” But a CHECK constraint will run defined logic on values and accept or reject them at the database level.

You can write CHECK constraints to do lots of validation:

- Ensure a number value is above or below a set point or within a range

- Run a REGEX(-ish) pattern on text input to ensure it complies

- Ensure the length of a string is in compliance

- Prevent the deletion of a row until some condition involving another table or value is satisfied

For example:

CHECK(username NOT GLOB '*[^a-z]*')

CHECK(length(password) >= 8)

CHECK(type IN ('user', 'admin'))

When included in a table definition, those CHECK constraints ensure that any value for the username value is comprised only of lower-case letters, the password value is at least eight characters, and the type value is only “user” or “admin” and nothing else. If any data comes in that violates those rules, the database will simply refuse to insert or update.

Additionally, I defined a bunch of triggers. So, for example, when records are deleted from some of the tables, I write the old data it to a “history” table as a crude form of versioning. Another example: if you try to delete the last record from the junction/interstitial table that links two records, it can cancel that to ensure that no record exists without being linked to something else.

These are things we normally enforce in the application/API layer, certainly (and sometimes even only in the UI layer, if we’re lazy). By moving these “back” to the data storage, I was hoping that I could “collapse” the application and data storage layers into one, and therefore make the database self-describing.

The goal was to be able to serialize this database structure – which now also happens to be a content model – to a text file (SQL DDL), and show it to an AI engine and tell it… “Build stuff that works with this.”

Here is the resulting SQL DDL. It’s pretty tight – even if you have SQL level access, it’s hard to get data in there that doesn’t work. This is accomplished via a set of CHECK constraints and TRIGGERS working together.

There were a couple edge cases I couldn’t work in. For instance: I wanted to ensure that a Note was assigned to at least one Person. However, there’s a problem that you have to insert the Note record before you assigned, so there will be a microsecond when it’s not assigned. I consulted ChatGPT and Claude, and they offered some really bizarre ways around this, using the tools SQLite has. (A stored proc would have solved this, but SQLite doesn’t have those.)

But, it’s pretty close. It’s a very well-defended and consequently well-described repository. By giving an AI engine the SQL DDL, it should understand the data and be able to build stuff with it… hopefully.

Now, if I provided this model definition to an AI agent, could it build something good from it?

This is what me and Claude ended up vibing:

flowchart TD

A(Full Web UI)

B(Web API)

C(Notifier)

D(Micro UI)

E(Static Site Gen)

G(Batch Process)

F{{CMS / Repository}}

F --> A

F --> B

F --> G

B --> C

B --> D

F --> E

style F fill:#FFe5dd,stroke:#DD4085,stroke-width:2px,color:#000,height:3rem;

The Repo is the aforementioned SQLite database

The Full Web UI is a Node/Express web app that provides data management functionality

The Web API is a REST API that provides remote access with token authentication

The Notifier is a Node background process that polls the web API and pops up a Windows notification when a new record is added or changed

The Micro UI is a small Electron app that provides nothing but the ability to type a note and search for a person to link it to

The Static Site Gen is a CLI process that wrote out all the Note records in a journal-like format (one output among many, I would assume)

The Batch Process is a scheduled process that searches for profanity and replaces it with a sanitized version (“f**k”, for example)

Now, I didn’t actually need of these – this was all just a big POC. (I was actually struggling a little to come up with different apps to write.)

But the point I was trying to prove was that if we have a well-described repository, that will assist AI in creating applications that operate on it. The Queen Bee can craft its own Worker Bees.

The results were… pretty good. Not perfect, but certainly promising.

However, I did realize pretty quickly that the SQL DDL was just not enough, sadly. The problem is that this described the data model, but it didn’t describe how I wanted to work with it as content.

For example: I gave the SQL database definition to Claude and told it: “Make me a Web UI for this.”

And I certainly got a web UI, but it was something like phpMyAdmin. Claude literally gave me a bare-bones UI to manage the tables, columns, and rows. For instance, to link a note to a person, I would need to add the Note, record the resulting ID, find a Person, record their ID, and then manually add the record in the junction/interstitial table. This is not what I wanted.

But to be fair to Claude, this was a web UI to manage the data as the database understood it. All the database understands was tables, columns, constraints, and triggers. And Claude did pretty good with this: I was gratified to see that Claude acknowledged all my CHECK constraints – for example, the apiKey column on the User table can only be (1) NULL, or (2) 32 characters. Claude correctly understood this and “elevated” this to the UI level to validate it there.

However, this clearly still didn’t manage the content in the way a human would want to manage it. And there’s no way to do this in the database definition – tables don’t have a place to state what the data means to a human.

So I determined that I need to provide that, and I wrote a short narrative explaining how a human would work with the data.

Here it is, in its entirety:

This is a database that is used to track information about people I know, including a running log of notes related to that person.

There are named users for the database. No one should be able to access the UI for the database until they provide a correct username and password.

I can enter people’s data into the database and tag them (friends, coworkers, relatives, etc.) I can also enter whatever birthday information I have about them: their full birthdate, just the month and year, or just the year.

I can add free-form notes, and associate the notes with one or more people. I can also tag these notes (phone call, meeting, request, etc). The notes are intended to be Markdown text.

I can use tags to find all the people or notes that are associated with it.

Whenever I change or delete a person or a note, the existing information is archived so that I always have a history of what the record was originally.

I tried to stay away from dictating any details of the UI, because this description was about the content model – what the data meant, and how I wanted to work with it – in conceptual terms.

So my description (my context) became two-part:

- The SQL DDL

- The “friendly” description of how I wanted to work with the data (as a text file)

Every time I wanted Claude to generate something, I gave it the SQL file, the text file, and then an additional description of what I wanted to build.

For example, here’s the “additional description” for the Batch Process. Using just that and the two other items mentioned above, it seemed Claude could build about anything.

All builds were done independently of each other. The only thing they had in common were the two files noted above.

In the end, I had a SQLite database file (the “Queen Bee”), and six folders, each containing an application that operated on the database (the “Worker Bees”). The worker bees didn’t know anything about each other, except for the exception noted.

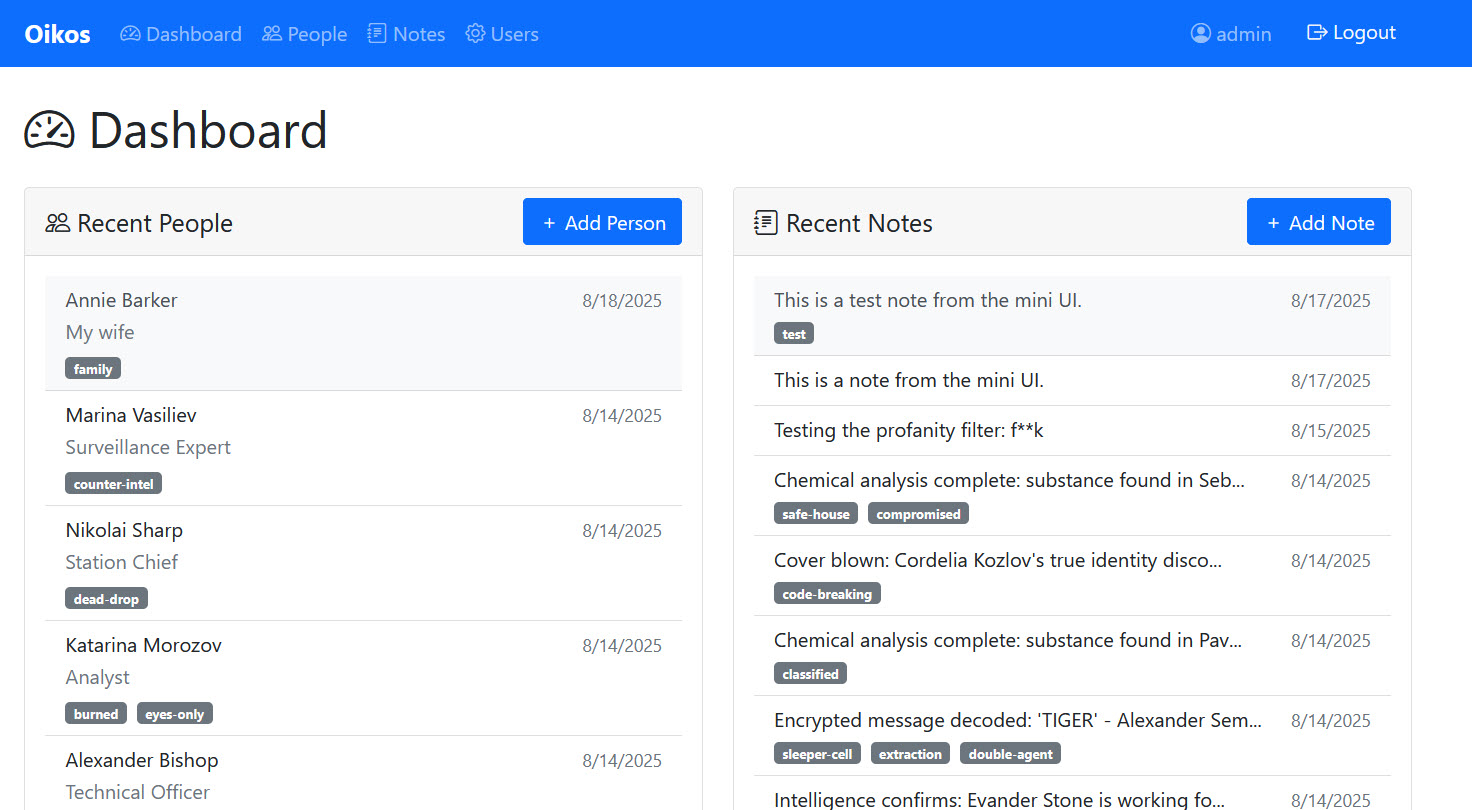

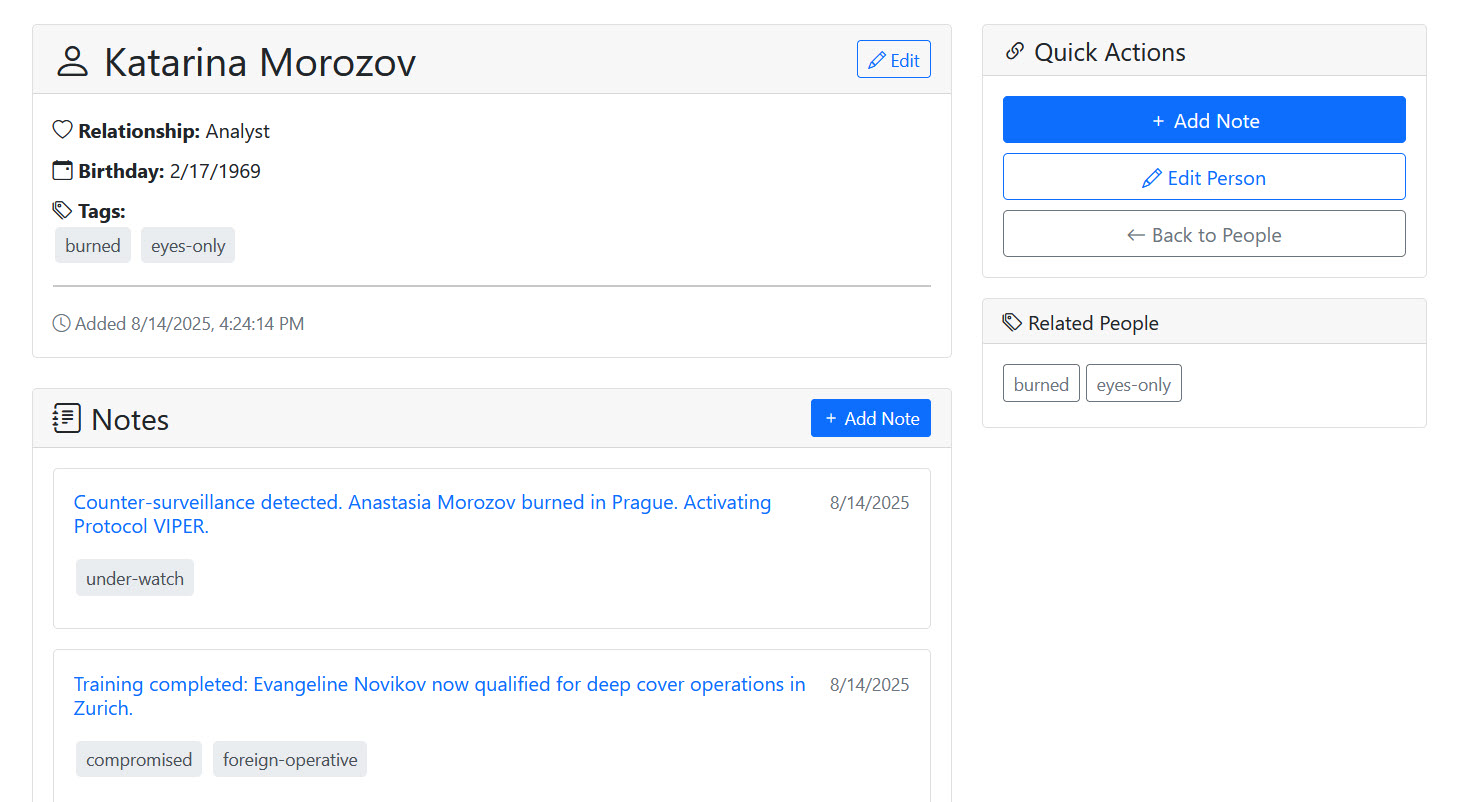

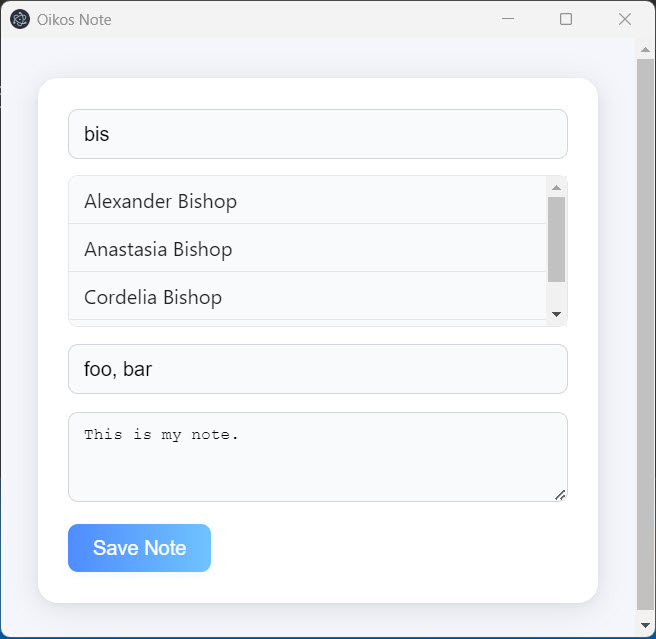

Here are some screencaps of what everything looked like (that had a UI or any worth getting an image of):

The Web UI “dashboard”

A person record in the Web UI

The Web/REST API

The Micro UI as a standalone Electron app

So, what did I learn from this? Well, it was a little all over the map, but here are some thoughts:

Something I already knew: data and content are not the same thing. Databases store “data.” You need a “Contentbase.” What the data is and what the data is intended to be used for are drastically different concepts, and computers can only reliably assume the former.

I still like the Queen Bee/Worker Bee analogy. Instead of my “CMS” being one big thing, I have a core repository and an… ecosystem of applications (a constellation? an array?), each doing their own thing, with only the repo in common.

The idea of a "well-described repository” is promising. But you’ll need to find a way to describe both the mechanics of the data storage and how you want to work with the data. As Kevin mentioned above, this is your context – your “contextual base.” You need to be sure that this well-rounded from both a raw data and intentional perspective.

The SQL DDL can be generated real-time, and the same is probably true for other repos as well. It wouldn’t be hard to provide a remote endpoint that would explain all the rules and intentions of the repository that your agent could connect to. However, you need to find a way to inject the “friendly” description of how you want to work with the data. As mentioned in my prior post, there’s no standard way to describe this.

If I was going stick with SQLite (I’m not), then I’d probably come up with some “meta table” that would store the friendly descriptions of the other tables, what they meant in terms of domain-level content objects, and how I would want to work with them. I’m not sure there would be a way to provided standardized access to this from the SQL level, but from the remote API level (which is where most access would come from), I could have an endpoint that returned a combination of friendly descriptions and SQL DDL.

Once I was satisfied that my data was secure (that my repository was “well-defended”), then I didn’t really care what Claude did with it. I don’t recommend getting callous with your data, but all of these apps took basically no effort from me, so I would have been happy to create them, use them, throw them away, and create new ones.

Consider this: could every user roll their own UI? We usually talk about “the UI,” and maybe we have a default…but what if I don’t like it? So long as the repository can defend itself, then could I just have some AI agent write me my own UI that I do like?

Pass-through identity will matter more. SQLite doesn’t have any user permissions (if you have access to the database file, you can do everything). That was a key issue in this case, because all my vibe-coded apps were connecting in “God mode.” In real-life, I’d use a database server that required login, and I would make them connect as actual database users that can be tracked and throttled, rather than funneling everything through the same user (as we tend to do with our applications).

Related to that, the idea of lots of independent worker bees doing content operations independently brings up questions around what non-developers might do. A human could always do something dumb, but AI will enable them to do dumb things at scale.

And where did this all leave me?

With a pretty big question, it turns out.

Frankly, I’m still a little unsure of where AI leaves the boundaries of CMS. Let’s assume I had a more full-featured database server, like SQL Server or Postgres – one that gave me stored procs, and more ways to make the database “well-defended and well-described.”

Could I implement an entire CMS purely in a database and call it good?

This, of course, is nothing new – this is how we did CMS back in the day. The entire idea of CMS, in fact, was the generalize content storage so we didn’t have to custom build databases for everything.

But with AI, we’re removing a lot of the work of custom-building things. If you have an agent to do the work for you, then do you really care if something is custom-built? Would it be easier to lock a content model down in a SQL database, and then just use AI to generalize everything into whatever output you wanted?

This comes back to a key point: most current CMS repositories say nothing about the model. They store it in a way that’s optimized for efficiency and adaptability, not intelligence, logic, intention, and discovery.

We don’t store an “articles” table. Instead we do something like this:

erDiagram

TYPE ||--o{ PROPERTY : has

OBJECT ||--o{ TYPE : "is instance of"

OBJECT ||--o{ OBJECT_PROPERTY : has

OBJECT_PROPERTY ||--o{ PROPERTY : "is instance of"

TYPE {

int id

string name

}

PROPERTY {

int id

int typeId

string name

}

OBJECT {

int id

string typeId

}

OBJECT_PROPERTY {

int int

int objectId

int propertyId

string value

}

This is very common repository model. (I think we call this an “object oriented repository,” but I’m sure the nomenclature is loose. Also, this assumes you’re using a relational database, which might not be true.)

Content in here doesn’t make any immediate logical sense, and it’s not intended to.

So why do we do this?

We do it to generalize, so we can adapt our repository to any “shape” of content – it doesn’t matter what you’re actually storing, this model will make it fit. Indeed, a big part of every CMS vendor’s business model is built off the idea that they’ll provide a general place to put content, adaptable to whatever your actual model is.

flowchart LR

a("Repository

(in generalized format)")

b("API

(interprets the generalized format)")

c("Editorial UI")

d("Output")

a-->b

b-->c

b-->d

style b fill:#cce5ff,stroke:#004085,stroke-width:2px,color:#000;

But are we just kicking the can down the road?

Since our repository could technically represent anything now, the customer just has to describe the content model somewhere else. We provide our vague, amorphous repository to the customer, and we have big configuration UIs and API/app layers where they can explain the model. Then we use that to extrude content into our generalized data repository.

…but what if we just described the content model at the repository? And then we pushed all the generalization off to AI? What if AI removed the labor overhead of making specific, form-fit repository and by doing so, made the repository the most efficient place to describe the model?

flowchart LR

a("Repository

(in specific, well-described format)")

b("Editorial UI via AI

(AI understands the specific format)")

c("Output via AI

(AI understands the specific format)")

a-->b

a-->c

style b fill:#cce5ff,stroke:#004085,stroke-width:2px,color:#000;

style c fill:#cce5ff,stroke:#004085,stroke-width:2px,color:#000;

I mean, we have to describe the content model somewhere, right? Why not describe it in the repository itself? And since our current databases – as demonstrated above – can’t understand intention, we’ll to find a way to let AI make sense of what the data does, not just what it is.

Are we coming full-circle back to bespoke databases? Has AI removed the comparative advantage to generalizing our repositories? Has AI made us less afraid of potential technical debt related to overly specific content models?

Will that be the CMS of the future? Just a really good repository that can be “well-defended and well-described”? And then we let AI handle everything else?

Well, this brings me back to the same argument I made in the last post.

I’ve just now spent a couple hours messing with databases and slowly wandered in a circle back to the same point.

I do this frequently.