I Ching

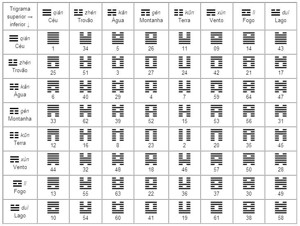

An example of an I Ching reference chart.

The best way to describe this is that it’s the ancient Chinese version of a tarot card deck.

The I Ching is a divination tool which dates back to perhaps as early as 1,000 BC. It consists of a table of 64 “hexagrams,” which correspond to an ordered combination of six lines which are either broken or unbroken (see image).

(This is essentially a six-digit base-2 numbering scheme. The “broken” and “unbroken” lines are two states, corresponding to a bit. Six bits gives 64 possibilities. Add two more lines, and you’d have the traditional 256 possibilities of what modern computing refers to as a “byte.”)

To use the I Ching, you think of a question to which you want clarity, then you generate random numbers/lines through various means – drawing straws, rolling dice, flipping coins, whatever – and correspond the results to a hexagram. Each hexagram has a word which is supposed to help resolve your question.

Some examples:

- Changing

- Unbroken

- Divided

- Heaven

Clearly, this requires a non-trivial belief in the supernatural and the power of divination.

I found several methods online of “reading” the I Ching. Some have you pick one hexagram, some have you pick more than one – there doesn’t seem to be a canonical way of doing it.

Much like a tarot deck, the I Ching is basically a collection of concepts, of which a subset is chosen somehow and then presented as a solution to a question or a prediction about the future. How they are interpreted seems to be wildly subjective. There’s a huge ecosystem of books and other tools for using and interpreting the results of the I Ching.

Not surprisingly, there are several websites which are online versions of the I Ching. Instead of rolling dice or flipping coins, computers generate random sequences for you.

I looked for a photograph of the original text, but I don’t think there is an original text. Much like the Hebrew Bible, the I Ching seems to be something that coalesced over time from oral tradition. There doesn’t seem to be a single source document. It likely appeared in written form in many places simultaneously.

The name translates roughly to “Book of Changes.”

Why I Looked It Up

I first read about it when researching ergodic fiction, which makes sense, since it’s text that is used as some kind of reference based on external inputs.

Then I found it again in a discussion of the writing of The Man in the High Castle. Supposedly, Philip K. Dick used the I Ching to help him write his novel.