Doing Something Poorly

I heard something that resonated with me the other day (I forget where I heard this):

Anything worth doing is worth doing poorly.

This, of course, is a play on this common saying:

Anything worth doing is worth doing well.

But, rather than making fun of an earnest, feel-good aphorism, what the former is saying is this: some things can be done just a little bit, and still provide benefit.

We tend to fall into ruts of perfectionism, like “I need to do this thing really well.” And sometimes that’s true. But sometimes it’s not.

Take exercise, for example. Some exercise is better than no exercise. So, if you go to the gym and put in a half-hearted effort, but you do something, then good for you. At least you went, got some physical benefit, and put yourself in the right mindspace.

Of course, this can be abused. You can get in the mode of putting in crap effort for everything and telling yourself, “Well, at least I did something.” But the other side of the coin is that your ability to put effort into something – like fitness – is going to ebb and flow, and don’t quit just because you’re in a place where you suck right now.

Keep moving forward, however slow and inconsistently. And if you can’t move forward, do something to just tread water until you can move forward again.

You don’t always have to be amazing. Sometimes just being something is valuable.

Update

Added on

During the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s been a lot of discussion about preventative measures and how much good they do. There’s an argument that it’s not all or nothing – doing anything will lower the risk of transmission, and doing something else will lower it more, and all of these effects are cumulative.

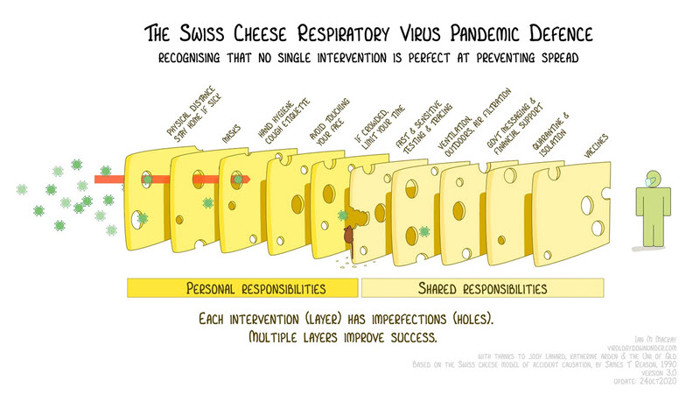

In particular, I loved this graphic that the NY Times reprinted in an article entitled “The Swiss Cheese Model of Pandemic Defense.”

(The graphic is supposedly from the Virology Down Under website, but I searched that site and couldn’t find it anywhere.)

The idea is that every preventative measure you take is like a slice of Swiss cheese. It has holes, sure, but if those holes don’t line up with the next slice in the stack, then transmission is stopped. Even if the holes of two adjacent slices do line up, you’ll eventually get to one where the holes don’t line up. So every slice, no matter how many holes it has, has the opportunity to stop transmission.

You don’t have to be perfect. You just have to stack imperfect habits and practices on top of each other.