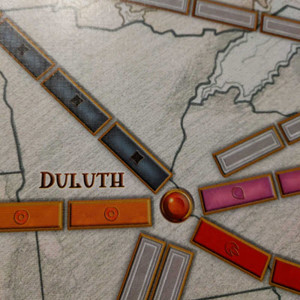

FYI, Duluth is not here. This is the Minneapolis/St. Paul metro. Duluth is actually up at the point of the lake up north. I have no idea how the game got Duluth way down here.

In March 2019, my wife and I started playing the now-classic board game Ticket to Ride. I’ve jotted down some notes and thoughts I had during this process – things I wish someone had explained to me, while I was learning it.

More than anything, this is just a place for me to organize my own thoughts on the game and its strategy.

(Note that my wife and I have only played the two-player game, so the below dynamics might change in larger games.)

You need to work the destination cards. When I started playing the game, I thought they were just “extra,” but they’re really the point. Your primary purpose in the game is to complete destination cards. You shouldn’t just be claiming random routes – indeed, the only reason to connect routes is to complete destinations. Many times, I’ve gotten more points from completed destination cards than I’ve gotten from completing routes.

When you draw destination cards (both at the start of the game and during the game), you can choose to put some back. Be careful of the ones you keep. You will have these for the entire game – once you decide to keep them, you are bound to them. And if you don’t complete them, you get penalized.

Because of the penalty, all destination cards are effectively worth double the stated point value. A 10-point destination will swing your score 20 points because you lose the points if you don’t win them. If you have 100 points otherwise, your score is 110 if you complete the route, and 90 if you don’t. There is no middle ground.

The 10-point longest route bonus is really just an incidental bonus. I don’t think 10-points is enough to alter a destination route strategy to pursue it. If you can get the bonus by easily connecting two other routes, then maybe, but I wouldn’t spend much effort chasing it.

At the beginning of the game, keep destination cards where the routes overlap. For instance, in one game, I kept Vancouver-Montreal and Seattle-New York (the most valuable destination card), because I knew that if I completed the former route, then I just needed to add two more short routes on either end to complete the latter route too.

When selecting destination cards, keep in mind (1) the cards in your hand, (2) the cards face up on the table, and (3) the “generic” routes between the destination cities. Often, you can pick a destination card where you can already complete the route through some combination of those three things.

Keep an eye on how many trains you have left when looking at a destination card. Late in a game, I was once tempted to go after some long route when I calculated that, even if I had the cards, I didn’t have enough trains left to physically complete the route.

Keep an eye on how many trains your opponents have left. When one of your opponents is down to 0, 1, or 2 trains, the game will end one turn later. If you’re working some grand strategy and need more than one route to complete it, the game might end suddenly, leaving you holding multiple destinations that you didn’t complete.

Always look for alternatives to playing locomotive wildcards. If the right color is face up, maybe wait a turn and take it rather than playing a locomotive. Play them only as a last resort.

Don’t be afraid to just claim long routes for the points, especially towards the end of the game, if you don’t want to take destination cards. You can take any route – it doesn’t have to be for a destination card, or connect to an existing route.

You can get a hint of what color someone is looking for by the face-up cards. If they don’t take any of them and draw from the deck instead, then you know what colors they’re not looking for.

You can get from Portland to Boston on all generic (non-color specific) routes, except for one six-car white route from Winnipeg-Calgary. If you have a destination card from the Northwest to Northeast (Seattle-New York or Portland-Boston), you need to start accumulating white cards early.

There is almost always more than one way into a city, even if it’s inefficient. Sometimes, you get so laser-focused on the “one way in,” that you overlook a perhaps less efficient way in. It might take more than one turn to complete, but the alternative is to spend turns drawing cards, so it’s likely a wash. For example, you might be desperately blowing turns on card draws to complete a six-car route, when you can can connect to the same city with two three-car routes, which you already have. Yes, the point total is less, but there’s value in completed a destination before getting blocked, and to start working on another one. Always ask yourself, “What is my Plan B,” because you may already have that.

The size of the cards is a problem. They’re hard to hold, and a lot of the game seemingly consists of shuffling cards around in your hand. Additionally, the cards are small enough that they’re hard to shuffle, and it’s critical that you shuffle them well, because they get discarded in sets of the same color. We ended up just dumping them face-down in the cover of the box, and sifting them in there to shuffle them.

As near as I can tell, the symbols on the cards are only to allow people with color-blindness to play without having to know the card color (they can correlate shapes, rather than color). The shapes can be otherwise ignored.

I set my trains up in nine groups of five, so I can easily tell how many I have left. My wife does not do this, which means estimating how much longer we have in the game can be tedious because I have to figure out how to count her remaining trains.

When you draw a face-up train card, you’re supposed to replace it before you draw again from the deck. Do this, because replacing the card essentially gives you a third draw. Draw #1 is a face-up card. Draw #2 is the replacement for that which you can decide whether or not to take, then, if you don’t take it, Draw #3 is the second card you take off the deck.

Later in the game, if you have some long routes that connect a lot of cities, you can often take three destination cards and find at least one that you have already completed, or can complete with a one- or two-car additional route. Just discard the other two. Occasionally, you can go through multiple destination card draws and keep just the one you’ve already completed.

Very late in the game, when you or your opponent are down to a half-dozen trains or so, and if you have completed all your destinations, it’s too dangerous to take destination cards because the game with be over in 2-3 turns. It’s never dangerous to draw cards. Just claim random routes for the points, or extend your longest route if you have a chance for the bonus.

Depending on your opponent, it might make sense to disguise your route building. Somewhat counterintuitively, this means building the route sequentially, from one end outwards. If you start building a route from both ends, it’s easier to figure out what you’re doing. Whereas, if you just start building a route for an origin city stretching to…somewhere, then there’s no way for your opponent to know where you’re going or when you get there.

A destination to Miami is not particularly desirable, because there are only three ways in, and they’re 4-, 5-, and 6-car specific-color routes. Additionally, there is no city that Miami can help you connect to – meaning, there are easier ways to connect any other two cities without going down into Miami and back.

Las Vegas is unique as the only city which has only two ways in – you can only come in from Los Angeles or Salt Lake City. Additionally, there is no destination card that includes Las Vegas, which means, unless someone is just claiming random routes for points, anyone claiming a route to Las Vegas is also planning to claim the other route out of Las Vegas. If this is you, make sure you can take both routes on consecutive turns to avoid being blocked, because you won’t be able to hide your intention.

Watch the critical path. If you need small, interconnecting routes which are crucial to a destination – and you don’t have a Plan B – consider getting them early against what it might reveal about your plans. Once, I had Montreal connected all the way through Los Angeles and up to Portland…and then my wife took the tiny Portland-Seattle route. There was no way around, and the Seattle-New York and Vancouver-Montreal routes I couldn’t complete cost me 42 points (really doubled, since I didn’t gain them, for an effective loss of 84).

The destination card values aren’t random – they’re the number of segments of the shortest possible path between the two cities.

Every color is represented equally on the board. Every color appears in exactly 27 route segments.

Remember that longer routes score exponentially more points. So, you have the cards to take a 5-car route, or a 3-car and 2-car routes, tend towards the longer one. A 5-car route is worth 10-points by itself, while the two smaller ones are worth 6-points together, plus it only takes a single turn. Only do the smaller routes if you need to connect the intervening city for some reason.

Kansas City-St. Louis is the most important route, from the perspective of Betweeness Centrality (it appears the most often when calculating the shortest paths between every city).

Before keeping a destination card, make sure you have enough trains. Sometimes you’ll draw three cards and you don’t have enough trains for any of them. In this case, you’ll need to just start claiming longer routes to rack up some points to offset the lost.

If you’re down to a small number of trains, an you think an opponent has unfinished destinations, try just taking some routes to burn through your trains and end the game, hopefully “stranding” them with unfinished destination cards.

Note: This is unfinished. I will continue to add to this over time.