You Only Laugh Twice: A Concise History of James Bond Spoofs

by Michael Monahan and Deane Barker

The Great Spy Boom of the 1960’s hit with all the power of a S.P.E.C.T.R.E.-hijacked nuclear warhead. Ground zero for this phenomenon was a chap named James Bond, swinging gentleman agent for Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Not surprisingly, his unprecedented box office success spawned a cottage industry of copycat productions. The super-spy genre was inundated with films hell-bent on claiming a piece of the throne from which 007 commanded the theaters, and by the mid-60’s a veritable army of secret agents were storming the battlements of local cinemas.

Bond spread his shadow across international boundaries, making him a public figure on the level of Presidents, the Royal Family – even The Beatles. As such, he was a ripe target for parody. Ultimately, spy comedies outnumbered genuine spy thrillers. The results ran the gamut from eye candy to brain Drano, with the lion’s share lampooning the conventions of the 007 films (suave hero, sexy women, implausible gadgets, and deranged global domination schemes) in the broadest possible terms.

The lasting appeal of these numerous spoofs isn’t surprising. While they tease the conventions of the James Bond adventures, they do so with obvious affection. The laughter comes from a shared enjoyment of the larger-than-life aspects of Bond, and the films don’t make fun of 007 and his fans as much as they remind us why we like the films in the first place.

Covering an area as vast as spy spoofs – even Bond-specific parodies – in a single article is a daunting task. With literally hundreds of films produced in the 60’s alone one can only hope to scratch the surface. The Italian spoofs (James Tont: Operazione U.N.O. and Due Mafiosi Contro Goldginger), Danish laugh-getters (Operation Lovebirds and Relax Freddy), and those weird Mexican wrestling hybrids are a little beyond the scope of this piece. We’ll have to scratch those hard-to-reach areas another time.

For now, we’ve chosen a handful of the genre’s most famous examples, and tossed in a few of the more colorful obscurities. In all, they help us appreciate the cinematic influence of our man Bond and level of fame and fascination he has ascended to in annals of Hollywood.

Our Man Flint (1965)

Our Man Flint followed on the heels of Goldfinger – the film that launched James Bond into the public consciousness – and it kicked off the Bond spoof wars with style. It’s essentially a one-joke film: How well can James Coburn out-Bond James Bond? Thankfully, the joke is a good one.

Our Man Flint followed on the heels of Goldfinger – the film that launched James Bond into the public consciousness – and it kicked off the Bond spoof wars with style. It’s essentially a one-joke film: How well can James Coburn out-Bond James Bond? Thankfully, the joke is a good one.

The world’s weather is going crazy and several secret agents have mysteriously turned up dead. In response, Z.O.W.I.E. (Zonal Organization for World Intelligence and Espionage) drafts Derek Flint (Coburn) to investigate.

Flint is the best at everything. He’s a martial arts master, an unsurpassable genius, and he lives with four gorgeous women. His apartment is a babe magnet of the highest order, and he brandishes his oily-smooth demeanor like a deadly weapon. How slick is he? When a man is found close to death, Flint unscrews a nearby light bulb, jams his superior’s hand in the socket, grabs his other hand, and uses the electrified human chain to start the man’s heart beating again. And, after an attempt on his life, Flint travels to Marseilles to find the person responsible. Why Marseilles? Because after having the poisoned dart analyzed, Flint finds traces of the ingredients common to a certain Bouillabaisse made only in Marseilles, naturally.

What makes Our Man Flint work is that it keeps one foot firmly planted in the Bond formula. Flint works alone, is ultra-slick with the ladies, and is a ruthless bastard. His adventures lead him on much the same step-by-step progression that the Bond films use. One clue leads him to another until he eventually gets captured and is taken to a remote island full of beautiful women and a bunch of scientists up to no good. There are several villains (including one played by Edward Mulhare, who would resurface almost 20 years later as Devon in Knight Rider) and a beautiful henchwoman who falls for Flint and changes sides. To make the formula complete, the island fortress explodes just after our hero takes a swan dive off a 300-foot cliff.

There are a few good-natured stabs at 007. When offered a Walther PPK and a briefcase containing 65 weapons, Flint produces a lighter which has “82 functions. 83 if you want to light a cigar.” And, early in the film, Flint stages a fight with fellow agent “Triple-Oh-Eight” (who, incidentally, is a dead ringer for Sean Connery). During the fight, Flint asks “Is this the work of SPECTRE?” “This is far beyond SPECTRE,” 0008 answers.

There are a few good-natured stabs at 007. When offered a Walther PPK and a briefcase containing 65 weapons, Flint produces a lighter which has “82 functions. 83 if you want to light a cigar.” And, early in the film, Flint stages a fight with fellow agent “Triple-Oh-Eight” (who, incidentally, is a dead ringer for Sean Connery). During the fight, Flint asks “Is this the work of SPECTRE?” “This is far beyond SPECTRE,” 0008 answers.

Our Man Flint can be considered the first salvo in the Bond spoof wars. Thankfully, Coburn and Company set a high standard, the memories of which carried kept the genre alive through some of dismal entries that followed.

The Second Best Secret Agent in the Whole Wide World (1965)

Originally filmed in England by director Lindsay Shonteff under the title Licensed to Kill, this film was picked up for U.S. distribution by Joseph E. Levine who slapped a new title on it and gave it a seriously swinging theme song, performed by Sammy Davis Jr.

Originally filmed in England by director Lindsay Shonteff under the title Licensed to Kill, this film was picked up for U.S. distribution by Joseph E. Levine who slapped a new title on it and gave it a seriously swinging theme song, performed by Sammy Davis Jr.

Soon after Swedish brothers August and Henrik Jacobson announce the completion of a revolutionary anti-gravity formula, August is assassinated by enemy agents. Henrik is scheduled to arrive in the U.K. to complete a sale of the process, dubbed Re-Grav, and the British government wants their best man on the case (the one who handled that “gold affair”) to protect him. Unfortunately, that particular agent is on assignment, but their second best man, Charles Vine (Tom Adams), is available. While protecting Jacobson from an independent criminal organization who want to kidnap the scientist, Vine must also contend with Russian assassins and unravel the secrets behind Re-Grav and August’s death.

While most spy spoofs of the period tried to establish their credentials by distancing themselves from 007, The Second Best Secret Agent… takes the opposite tack, happily embracing comparisons to poke fun at it’s own budgetary constraints. So Charles Vine may affect the sartorial elegance of James Bond, but his department is obviously on a Harry Palmer budget (much like the film itself).

Dark, handsome, and physically substantial, Tom Adams does well as a Sean Connery substitute. Like Connery, his working class roots show under the fine cut of his suit. Smooth enough to cruise a society party, he also looks burly enough to be a bar room brawler, capable of punching someone through a wall.

The film sets up all the usual targets for spoofing the Bond series: impossibly pliant women, cross-dressing Asian killers, even silly names (“She He” for the Asian killer, “Sadistikov” for a Russian assassin). But it also tosses in some unexpectedly insightful curves. As the film piles up an everything-but-the kitchen-sick set of plot twists, writer/director Shonteff takes the time to happily blow a raspberry at all the critics who condemned the violence of the Bond films as “sadistic.” In the course of numerous showdowns with the enemy, Vine’s “license to kill” is (rightfully) portrayed as a ticket to shoot numerous unarmed agents in the back.

The film sets up all the usual targets for spoofing the Bond series: impossibly pliant women, cross-dressing Asian killers, even silly names (“She He” for the Asian killer, “Sadistikov” for a Russian assassin). But it also tosses in some unexpectedly insightful curves. As the film piles up an everything-but-the kitchen-sick set of plot twists, writer/director Shonteff takes the time to happily blow a raspberry at all the critics who condemned the violence of the Bond films as “sadistic.” In the course of numerous showdowns with the enemy, Vine’s “license to kill” is (rightfully) portrayed as a ticket to shoot numerous unarmed agents in the back.

Because of the film’s limited budget, outdoor scenes generally play better than interiors, which are often lit in a hodge-podge of murky shadows and over-bright hot spots. The editing, particularly during action sequences, is sometimes crude and confusing. But despite questionable production values, the film’s sloppy enthusiasm is contagious.

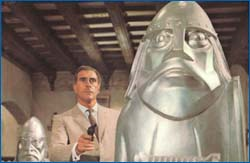

Deadlier Than the Male (1966)

Richard Johnson stars as the pulp sleuth Hugh “Bulldog” Drummond in this flashy, Bondian update. Drummond, an investigator for Lloyd’s of London, is in hot pursuit of Carl Peterson and his squad of sexy female killers. Through a systematic campaign of assassination, Peterson has maneuvered himself into a prime position to grab the oil concessions to the country of Akbar. Drummond must save Akbar’s ruler, who stands as the final impediment to Peterson’s plan.

Richard Johnson stars as the pulp sleuth Hugh “Bulldog” Drummond in this flashy, Bondian update. Drummond, an investigator for Lloyd’s of London, is in hot pursuit of Carl Peterson and his squad of sexy female killers. Through a systematic campaign of assassination, Peterson has maneuvered himself into a prime position to grab the oil concessions to the country of Akbar. Drummond must save Akbar’s ruler, who stands as the final impediment to Peterson’s plan.

When Broccoli and Saltzman were casting for Dr. No, Richard Johnson was on the short list of actors being considered for James Bond. His qualifications are definitely on display in Deadlier Than the Male, but so are his shortcomings. While he makes a smooth, cultured hero – tossing fists and bon mots with equal facility – his somewhat fatherly attitude and military bearing, while perfectly suited to Drummond, are no match for Connery’s youthful jet-set cockiness.

In mixing humor with genuine thrills, the film makers appear to have used Goldfinger for their model. Like the Bond film, Deadlier Than the Male contrasts the old world elegance of fire-lit, oak-lined studies and cozy leather chairs with harshly modern space age design and gleaming robotic technology.

Nigel Greene is a perfect nemesis: cold, arrogant, and physically imposing. Unlike the many cardboard villains of the genre, Greene oozes a sense of real danger. His murderous magpies, Elke Sommer and Sylvia Kosina, are both familiar players in the spy world, and add a ruthless glamour to the proceedings. Some critics were put off by the variety of clever murders the film portrayed. In retrospect, it’s clear that the film effectively bridged the morbid, death-based humor of The Avengers and Dr. Phibes.

Nigel Greene is a perfect nemesis: cold, arrogant, and physically imposing. Unlike the many cardboard villains of the genre, Greene oozes a sense of real danger. His murderous magpies, Elke Sommer and Sylvia Kosina, are both familiar players in the spy world, and add a ruthless glamour to the proceedings. Some critics were put off by the variety of clever murders the film portrayed. In retrospect, it’s clear that the film effectively bridged the morbid, death-based humor of The Avengers and Dr. Phibes.

The climatic battle between Drummond and Peterson, staged on a huge mechanical chess board, is one of the finest moments in a non-007 spy film. In fact, one of these chess pieces would later pop up, peering over Christopher Lee’s shoulder, in the pre-credit sequence of The Man With the Golden Gun.

Where the Bullets Fly (1966)

In the second Charles Vine film, enemy agents, under the guidance of a criminal mastermind named Angel, are attempting to steal a sample of the government’s revolutionary new discovery: a light-weight, radiation resistant substance called spurium which would allow for the construction of nuclear powered aircraft.

Slicker than the first film, and very colorful, Where the Bullets Fly benefits from a confidence bred of box office success. The appearance of popular comics Sydney James and Wilfrid Brambell (Paul’s “clean” grandfather in A Hard Day’s Night) signal a shift to a more standard form of British comedy. In all, this is an entertaining follow-up, but it lacks some of the first film’s personality. Vine’s rougher edges have been smoothed off to pure Bond.

John Gilling is a dynamic visual director whose credits include numerous Saint episodes, as well as topnotch Hammer horror films – including the nightmare-inducing Plague of the Zombies. The action sequences are particularly well handled – but the real highlight is a rather pedestrian exposition scene that suddenly switches perspective to a woozy point-of-view shot from the office cat!

Hammer veteran Michael Ripper plays Angel as a tweedy, pint-sized version of Auric Goldfinger. The Goldfinger influence continues to the film’s airborne climax, which finds Mr. Angel gaining his wings the hard way.

A pre-credits sequence in which Vine dresses in women’s garb to thwart a missile attack on Parliament is clearly lifted from the widow-punching episode in Thunderball. Early in the film, Angel’s agents attempt a hijacking of the spurium aircraft, using hypnosis to gain control of the crew – another sequence modeled on the Bond film.

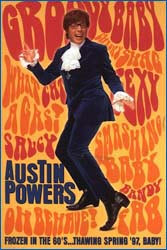

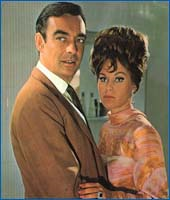

The Silencers (1966)

Of all the 007 wannabes that flooded the cinemas in the mid-60’s, perhaps the most famous is Matt Helm. As embodied by Dean Martin, the perpetually tipsy superspy would eventually appear in a quartet of garish, increasingly outrageous exploits between 1966 and 1969: The Silencers (1966), Murderer’s Row (1966), The Ambushers (1968), and The Wrecking Crew (1969).

Of all the 007 wannabes that flooded the cinemas in the mid-60’s, perhaps the most famous is Matt Helm. As embodied by Dean Martin, the perpetually tipsy superspy would eventually appear in a quartet of garish, increasingly outrageous exploits between 1966 and 1969: The Silencers (1966), Murderer’s Row (1966), The Ambushers (1968), and The Wrecking Crew (1969).

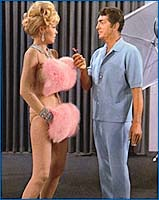

Like the early Bond films, the Matt Helm films are aimed at adults. Though the action is childish, the sophisticated strip club settings, booze culture humor, and sexual by-play are all aimed directly at grown ups. The jokes are risqué, the women are ripe, and the numerous hangover gags cry out for a rim shot.

In The Silencers, Matt Helm is pulled out of retirement to thwart a scheme by the criminal organization Big O to sabotage a nuclear test, raising a cloud fallout that would wipe out all life in the Western hemisphere. Along for the ride is Gail Hendrix (Stella Stevens), a charming klutz whom Helm suspects is really a Big O agent.

Screenwriter Oscar Saul utilized material from two of Donald Hamilton’s books, “Death of a Citizen” and “The Silencers,” making this the most densely plotted and hence most satisfying of the four films.

It also has the finest cast. From the corpulent Victor Buono – perched on his rotating dais, chirping fake Chinese like an enormous canary – to the dark and curvaceous Daliah Lavi – sporting a space age mushroom hairdo and purring throaty, sinister endearments – this is the most consistently well-cast film in the series. Even secondary roles are filled by talented Hollywood stalwarts like Robert Webber, Cyd Charisse, and Arthur O’Connell.

Best of all is Stella Stevens, who takes a typical dumb-blonde role and spins it into an engaging piece of physical comedy. As a naive but accident-prone innocent, Stevens feeds Dino the kind of slow-burn material that worked so well with his old comedy partner, Jerry Lewis. There’s a genuine warmth and camaraderie between the players that would never quite be re-captured in the series.

While the film was greeted enthusiastically by the ticket-buying public, members of the Matt Helm Fan Club picketed the film’s opening. Hamilton’s story would receive a more faithful, if unofficial, adaptation in “Fortune City,” an episode of the TV series It Takes a Thief. The episode featured a pre-Hart to Hart teaming of Robert Wagner and Stephanie Powers.

Murderer’s Row (1966)

Another Matt Helm film, Murderer’s Row followed The Silencers in quick succession. In this one, Big O chief Julian Wall (Karl Malden) plans to use a kidnapped scientist’s new super-weapon to destroy Washington D.C. Matt Helm travels to the Riveria and joins forces with the missing scientist’s daughter (Ann-Margret) to find her father.

Another Matt Helm film, Murderer’s Row followed The Silencers in quick succession. In this one, Big O chief Julian Wall (Karl Malden) plans to use a kidnapped scientist’s new super-weapon to destroy Washington D.C. Matt Helm travels to the Riveria and joins forces with the missing scientist’s daughter (Ann-Margret) to find her father.

While The Silencers had enough story to give it a faint whiff of legitimacy, Murderer’s Row doesn’t have enough plot to fill a shot glass. But it almost makes up for it with madly mod production values. The opening credits are a delirious op-art dream of solarized go-go girls and concentric circles set to a driving Lalo Schiffrin instrumental theme. The cinematography, by Sam Leavett, is the best in the series – rich color wrapped in form-fitting shadow. The flashy-trashy fashion and set design are likewise eye-catching.

In Like Flint (1967)

The ridiculously infallible Derek Flint bounds back into action to thwart the female leaders of media and fashion in their bid for world conquest. From Fabulous Face, their space age isle of Lesbos in the Caribbean, the all-woman army is poised to upturn the balance of sexual power by seizing an orbiting atomic weapons platform (a move Flint condemns, in scenes cut by the studio, as merely flipping the same corrupt coin). The first step in their plan involves replacing the President of the United States (Andrew Duggan) with a surgically created double (“An actor as President?”, marvels Flint), who promptly fires Lloyd Cramden (Lee J. Cobb), after staging an embarrassing sexual scandal involving the Z.O.W.I.E. chief.

The ridiculously infallible Derek Flint bounds back into action to thwart the female leaders of media and fashion in their bid for world conquest. From Fabulous Face, their space age isle of Lesbos in the Caribbean, the all-woman army is poised to upturn the balance of sexual power by seizing an orbiting atomic weapons platform (a move Flint condemns, in scenes cut by the studio, as merely flipping the same corrupt coin). The first step in their plan involves replacing the President of the United States (Andrew Duggan) with a surgically created double (“An actor as President?”, marvels Flint), who promptly fires Lloyd Cramden (Lee J. Cobb), after staging an embarrassing sexual scandal involving the Z.O.W.I.E. chief.

The comedy is broader this time around, with Flint’s high jacking of a plane bound for Cuba, to the accompaniment of a Communist anthem (complete with on screen lyrics and a bouncing red star) as a particularly extreme example. As before, Flint is a master of every subject, prepared to discuss feminist politics with style-conscious Amazons, ballet with the KGB, or dining arrangements with trained dolphins. The fact that Coburn can play the silly bits with conviction, and still retain a sense of absolute authority in the action sequences is a testament to his screen charisma.

The familiar style and settings initially promise business as usual. But Jerry Goldsmith’s lilting, minor key theme, a recurring theme of betrayal, and a cluster of wistful, resigned performances (especially Lee J. Cobb’s) hint at deeper meaning running just under the surface. This maturity is further emphasized visually by staging a good amount of the action at night, or in shadow.

The film’s sexual politics are hopeless garbled. But while it never manages to reconcile it’s feminist sympathies with a bikini and hot-pants fashion sense, the very inclusion of these elements in the notoriously sexist superspy genre sets the film apart.

A third sequel,_ The Bride of Flint_, was announced, but never filmed. Also left unrealized was a proposed television series, though a pilot script, titled “Flint Lock” was commissioned from fantasy author Harlan Ellison. When a small screen version of the character finally surfaced, it was in the form of an execrable 1976 TV movie titled Dead On Target: Our Man Flint, featuring transcendentally smug Ray Danton as Flint.

Somebody’s Stolen Our Russian Spy (1967)

When Colonel Yevtushenko, a captured spy being returned to Russia under British protection, is hijacked on the high seas by Chinese & Albanian agents, Charles Vine is called in to retrieve him. Captured during a rescue attempt, Vine finds himself imprisoned in castle fortress deep in the heart of Albania. Effecting an escape, and following a wild tank and speedboat chase, Vine returns Yevtushenko to his people.

After dutifully protecting the soccer fields and back alleys of London for two films, Charles Vine finally gains an international playing field in this one. But, while this gives him a chance to strut some very Bondian stuff, he still works better on his own turf. There’s a slightly underdog, home-team charm to Vine’s London-based adventures that gets lost when he graduates to global secret agent. Tom Adams makes the most of the opportunity to expand his action man status, impressively turning commando during the climatic breakout, in what could easily pass as an audition for 007.

If the previous film had used Goldfinger and Thunderball as its touchstones, this final Charles Vine adventure clearly leans on From Russia With Love for narrative support. In addition to a more complex structure, filled with numerous shell games and quadruple crosses, the film lifts both the helicopter and boat chase episodes of FRWL for its own climax, mixing them together into a single extended action sequence wherein Vine blasts a pursuing chopper out of the sky while piloting a stolen speedboat. If the film had a third act, they just might have managed a worthy sequel.

Unfortunately, once Vine crashes out of the enemy’s stronghold, the film looses shape, and just sort of putters around until it stops. The addition of a “lost patrol” of British soldiers still fighting the second World War pushes the film from playfully silly to painfully stupid, which is a pity. While Adams never achieved the easy charm of Connery, he could play a smooth, dangerous man with conviction; a strength which helped agent Charles Vine stand out from the pack of imitators. For a guy who began his career gleefully cultivating comparisons to 007, he didn’t do too badly. He deserved a better swan song.

Tom Adams affiliations with espionage and adventure would continue throughout his career – though usually as the villain. He appeared in the Raquel Welch spy adventure, Fathom (1967), and Subterfuge (1969) – an espionage thriller with Gene Barry and Joan Collins. He worked again with Second Best Secret Agent… director Lindsay Shonteff in The Fast Kill (1972) , a violent caper movie, and would later appear in U.K. televisions’s Spy Trap, as well as an episode of Remington Steele.

Lindsay Shonteff would use 007’s box office revival in the late 70’s to launch a series of cartoon-ish spy spoofs featuring secret agent Charles Bind. In addition to tweaking his famous spy’s last name, he re-christened old boss Stockwell as Rockwell, and cast Geoffrey Meek (the Minister of Defense in the Bond films of the 70’s and 80’s) in the role. Nicky Henson portrayed Bind in No. One of The Secret Service (1977), ex-New Avenger Gareth Hunt picked up the mantle in No. One: Licensed to Love and Kill (1979), and Michael Howe finally closed the show with No. One Gun (1990), by which time the increasingly budget-strapped series was clearly sucking fumes.

Of these latter day spy spoofs, No. One: Licensed to Love and Kill is the arguably the best – or at least the most fun. Gareth Hunt has the sly delivery that makes this type of role work, and his desert-dry aplomb is set against as outrageous as set of characters and situations as the undiscriminating fan could hope for. One scene in particular really buries the needle on the goofy-meter. While searching for clues at a strip joint, Bind finds himself menaced by a murderous go-go dancer sporting razor blades at the end of her spinning tassels!

Fans of The Second Best Secret Agent… will also enjoy Shonteff’s numerous references to the parent film, including a re-staging of the She-He fight, and Bind’s resurrection of Charles Vine’s favorite pick up line: “Do you make a habit of being the most beautiful girl in the room?”

Casino Royale (1967)

Before you go getting excited, be warned that Casino Royale has very little to do with the Fleming novel from which it takes its title. (See the FAQ for details on how this film came about.) Also be warned that the film is lacking a very important ingredient of any comedy – namely, comedy.

Before you go getting excited, be warned that Casino Royale has very little to do with the Fleming novel from which it takes its title. (See the FAQ for details on how this film came about.) Also be warned that the film is lacking a very important ingredient of any comedy – namely, comedy.

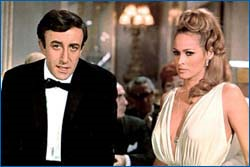

David Niven is Sir James Bond, evidently retired. When M is murdered (don’t blink or you’ll miss it), Bond comes back to foil Le Chiffre’s gambling operation. He recruits Evelyn Tremble (Peter Sellers) to beat the villain at the baccarat tables. Ursula Andress checks in as Vesper Lynd, and Woody Allen is…well, no one can be quite sure.

Eight writers combined for this film, and it was put together by five different directors each shooting a separate sequence (including acclaimed director John Huston, who also appears in a small role as M). The sequences range from the utterly pointless – Bond at M’s home with his widow and eleven daughters, none of whom can manage to seduce him – to the downright hallucinogenic – Mata Bond (the daughter of 007 and Mata Hari, natch) at some kind of clinic in Berlin which comes off looking like a bad acid trip. All of this comes to a climax (?) with a riot in the Casino Royale involving a tribe of Indians, a roulette wheel that flies around spewing out laughing gas, and Woody Allen hiccuping mini-mushroom clouds from a nuclear bomb he’s swallowed.

Casino Royale is a mind-numbingly stupid jumble of plot twists that go nowhere and usually get left dangling. This is compounded by the film’s 130 minute running time. But don’t fall asleep lest you be jolted awake by some of the more annoying (yet oddly acclaimed) background music in cinema history.

The hi-lights are few. “The Look of Love” by Dusty Springfield was nominated for a Best Song Oscar. Woody Allen is quite good towards the end, and Orson Wells would have made a great Le Chiffre if the film had ever been done seriously. And then there’s the gorgeous dark-green Bentley that Niven whizzes around in, but that’s about it.

The hi-lights are few. “The Look of Love” by Dusty Springfield was nominated for a Best Song Oscar. Woody Allen is quite good towards the end, and Orson Wells would have made a great Le Chiffre if the film had ever been done seriously. And then there’s the gorgeous dark-green Bentley that Niven whizzes around in, but that’s about it.

Some, however, have defended the film on the dubious grounds of its own perversity. Casino Royale exploited the neon-colored, polyester jacketed 60’s attitude far beyond the bounds of good taste. At a certain point, it appears the filmmakers were so far gone they just tried to push the envelope and ended up busting it wide open. For this reason, there are a few Casino Royale fans out there, some of which are paradoxically rabid Bond fans at the same time.

A Man Called Dagger (1967)

Paul Mantee stars as Dick Dagger, a not-so-superspy out to stymie mind-controlling Nazi Jan Murray (!?!?). This no-budget disasterpiece is notable primarily for the crazy-quilt of talent that put it together. Director Richard Rush had come from motorcycle movies, and would go onto The Stunt Man. Connery-jawed Paul Mantee is most famous for his role as Robinson Crusoe on Mars. Co-star Terry Moore is best known for dating big ape Mighty Joe Young – also big ape Howard Hughes. Add to that sit-com queen Sue Anne Langdon, borsht-belt comic Jan Murray, pre-Bond (but post-Eegah!) Richard Kiel, and a musical score by Steve Allen – and you got yourself one wacky spy movie.

Some Girls Do (1968)

As so often happens within the realm of mega-criminals, the news of Carl Peterson’s death has proven premature and Bulldog Drummond is back in action. Using sonic weapons and an army of robotic women, he returns to sabotage the test flight of a new SST jet liner. Drummond tracks Peterson to his luxury hotel/headquarters, scrambles the circuits of his deadly femme-bots, and blows the place to smithereens.

As so often happens within the realm of mega-criminals, the news of Carl Peterson’s death has proven premature and Bulldog Drummond is back in action. Using sonic weapons and an army of robotic women, he returns to sabotage the test flight of a new SST jet liner. Drummond tracks Peterson to his luxury hotel/headquarters, scrambles the circuits of his deadly femme-bots, and blows the place to smithereens.

Lighter and brighter than the first film, Some Girls Do is swift, pop entertainment. Trading in the twilight shadows, rustic surroundings and overbearing brass of Deadlier Than the Male, the film bathes itself in Spanish sunshine, mod color and mellow, fuzz-tone guitar. The explosive finale features effects on a par with Bond, and the candy-coated color scheme invites the eye to shamelessly indulge itself.

John Villiers (Bill Tanner in For Your Eyes Only) steps in for Nigel Greene as Carl Peterson . He’s not as impressive an enemy, more of a brat than a serious threat, his arrogant veneer barely concealing an underlying petulance. But he scores big points for his hilariously snobbish dialogue.

In fact, class issues get big laughs in this one, from the supercilious Miss Mary (Robert Morley) who runs an information gathering cooking school, to Peterson’s inspiration for the scientific marvels of his femme-bots (bad service in hotels). In the midst of his reverie over the impeding success of his scheme, and the rich rewards soon to follow, Peterson is even accused of being monstrous – not for his deadly deeds, but for talking about money “Like a tradesman.”

The Drummond films are unique for the period in that women are not just there for decoration – they genuinely drive the plots. This is no-doubt due to the long-running partnership of producer Betty Box and director Richard Thomas. In films like Agent 8 3/4 (a.k.a. Hot Enough for June) and Nobody Runs Forever (a.k.a. The High Commissioner), the team emphasized the role of women on both sides of the espionage battle. In Some Girls Do, women both save the day and pluck the prize from under Drummond’s nose at the end.

The Ambushers (1968)

About 25 years before The X-Files postulated the existence of government-built flying saucers, Matt Helm was chasing a stolen prototype to sunny Acapulco. Joining Helm is top I.C.E. pilot Jamie Summers (Janice Rule), who suffered unspeakable torture at the hands of saucer-napping Leopold Casellias (Albert Salmi).

About 25 years before The X-Files postulated the existence of government-built flying saucers, Matt Helm was chasing a stolen prototype to sunny Acapulco. Joining Helm is top I.C.E. pilot Jamie Summers (Janice Rule), who suffered unspeakable torture at the hands of saucer-napping Leopold Casellias (Albert Salmi).

If Murderer’s Row was a step down from the film before, The Ambushers was a swan-dive into the abyss. Perversely, the film’s boundless ineptitude, relentless stream of booze and bosom gags, and daffy flying saucer plot (D.T. rather than E.T.-inspired) make this the most well-known of the series. Not surprisingly, The Ambushers was savaged by the critics, and even the most forgiving fans were put off by the increasingly puerile antics of their erstwhile hero.

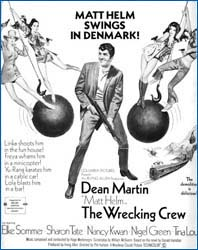

The Wrecking Crew (1969)

With The Wrecking Crew, the Matt Helm crew made a concerted effort to revive the popular formula of The Silencers.

With The Wrecking Crew, the Matt Helm crew made a concerted effort to revive the popular formula of The Silencers.

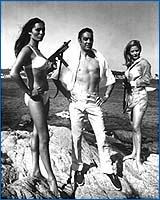

Helm is once again pulled out of hung-over hibernation, this time to deal with a $10 billion gold robbery which threatens the economic stability of the West. Count Contini (Nigel Green) and his beautiful courtesan Linka Karensky (Elke Sommer) have engineered the heist from their chateau in Denmark. They do this under the aegis of Red Chinese agent Yu Rang (Nancy Kwan) and her cohorts, who use a bordello – The House of Seven Joys (a working title for the film) – as a front for their activities. Helm is paired with I.C.E. agent Freya Carlson (Sharon Tate), an overzealous cadet who naturally works her way under his skin.

The Wrecking Crew is a tight, fun ride. While it lacks the budget of The Silencers, it’s also lighter on its feet, a nimble little spoof packed with offbeat action and an attractive, self-deprecating spirit. Dean Martin seems renewed, no doubt thanks to the attentions of his director, and performs his duties with a smooth, professional grace.

Sharon Tate is a shade too shrill and brittle for a role designed after Stella Stevens’ Gail Hendrix. But Nancy Kwan, Elke Sommer, and Tina Louise more than compensate. And Nigel Green’s ramrod bearing and the archly sophisticated airs prove to be the perfect foil for Dino’s cozy, “what-me-worry” slouch. With the added elements of cultural and class tension, their sparring exchanges actually strike some sparks.

The end credits promised another round with The Ravagers, but for Matt Helm, this was last call. Dean Martin wasn’t interested in committing himself to another film. He was already busy with his weekly television show, and he preferred westerns to spy movies any day. And besides, he wanted to spend more time practicing his golf swing. So Matt Helm, the bar stool Bond, the pagan god of the tiki lounge, quietly finished his drink, tipped the waitress, and walked off into night.

The Nude Bomb (1980)

Bond spoofs took a major nap after the late 60’s. This likely coincided with the nadir of the real Bond series, but like hecklers in a crowd, the spoofs came back as soon as their target did.

Bond spoofs took a major nap after the late 60’s. This likely coincided with the nadir of the real Bond series, but like hecklers in a crowd, the spoofs came back as soon as their target did.

With the astonishing box office resurrection of 007, represented by the worldwide blockbuster status of _The Spy Who Loved M_e (1977) and Moonraker (1979), studios once again began rummaging through their dusty old piles of secret agent properties looking for a quick buck. What more natural a choice than the popular TV Bond spoof of the 60’s: Get Smart. With Don Adams, the original Maxwell Smart, in place as the bumbling Agent 86, the prospects looked sunny. Unfortunately, the resulting big screen revival, titled The Nude Bomb (1980), has all the style and class of a roller disco. Like the period which spawned it, the film is bright, colorful and flat.

The streaker-era plot finds Maxwell Smart out to thwart a KAOS plan to detonate a newly developed weapon which would leave every man, woman, and child completely nude and at the mercy of outre designer Norman Sansavage (Vittorio Gassman), whose secret mountain headquarters is guarded by jumpsuited sentries and a really, really big zipper.

The film opens well, with a Moonraker-inspired parachute sequence that manages to be both thrilling and silly in the old Get Smart tradition. But things quickly go wrong as soon as Smart has his feet on solid ground. Apparently the filmmakers could only secure the rights to portions of the Get Smart creation. Maxwell Smart still communicates with headquarters via his trademark shoe-phone, but headquarters is now designated as P.I.T.S. While the classic TV series pit Control against Kaos (which makes sense, as they represent diametrical opposites) the film pits P.I.T.S against the old enemy (which is…well…pitiful). No mention is made of Control, Agent 99, Max’s marriage, or his children (the twins were born in the fifth season).

There are bright spots. Most of the actors are old pros, guaranteeing the bantering dialogue scenes have the required snap. Co-writer Bill Dana also has a few bright moments as fashion designer Jonathan (Dana stood in for an ailing Don Adams in one episode of the old series: Ice Station Siegfried). Best of all is a sequence where Smart gives chase to a KAOS agent from behind the wheel of his motorized desk, providing the film with a startlingly goofy image.

But ultimately, the film is less representative of the beloved television show that inspired it, and more a reflection of the same callous, coke-fueled Hollywood system that spawned The Car and Jaws 2 in the same period. Nowhere is this better illustrated than during a foot chase – which just happens to take place all through the backlots of Universal Studios, fresh from its transformation from production facilities to movie theme park tourist attraction. This is product placement at its most arrogant, amounting to nothing less than a 10-minute commercial for the Universal Studio’s Tour.

But ultimately, the film is less representative of the beloved television show that inspired it, and more a reflection of the same callous, coke-fueled Hollywood system that spawned The Car and Jaws 2 in the same period. Nowhere is this better illustrated than during a foot chase – which just happens to take place all through the backlots of Universal Studios, fresh from its transformation from production facilities to movie theme park tourist attraction. This is product placement at its most arrogant, amounting to nothing less than a 10-minute commercial for the Universal Studio’s Tour.

But even this obvious corporate plug doesn’t completely smother the movie’s good will. There are, in fact, some real laughs along the way. However, despite a handful of inspired moments, it simply goes on for too long. The old series consistently did just this type of story in 30-minutes. The production values are on a par with TV movies of the period, and besides – too many familiar, well-known elements of the show were replaced by colorless substitutes (including Emanuelle star, Sylvia Kristel!) to make even the best segments wholly satisfying.

No Control, no 99, no dice…sorry about that, Chief.

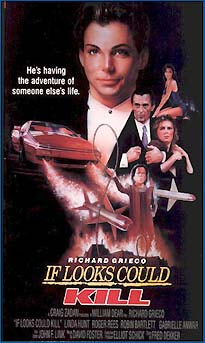

If Looks Could Kill (1991)

As the reigning teen idol of 21 Jump Street and Booker, Richard Grieco tested the big screen in this wholly underrated farce. If Looks Could Kill should be admired for the ripping off virtually every Bond film with shameless abandon while thankfully staying away from the slapstick of Spy Hard or the hallucinogenic stupidity of Casino Royale.

As the reigning teen idol of 21 Jump Street and Booker, Richard Grieco tested the big screen in this wholly underrated farce. If Looks Could Kill should be admired for the ripping off virtually every Bond film with shameless abandon while thankfully staying away from the slapstick of Spy Hard or the hallucinogenic stupidity of Casino Royale.

Grieco is Michael Corbin, high-school slacker (even though Grieco was 26 at the time) who goes to Paris with his French class for a much-needed foreign language credit. Naturally there’s a super-spy booked on the same flight who just happens to have the same name. Convenient confusion results, the spy Corbin is killed, and the student Corbin is suddenly the target of a maniacal would-be dictator (Roger Rees), his diminutive assassin (Linda Hunt), a big-breasted femme fatale named “Aureola” (wink, wink), and a large man with a steel hand who grunts a lot and bumbles around with the same endearing buffoonery that made Jaws so popular.

Bond references hurled at the viewer en masse. Taken by the British Secret Service to their laboratory, Corbin is given the traditional gadgets: explosive chewing gum, x-ray glasses, and a Lotus Esprit complete with tuxedo in the trunk. Before long he’s – you guessed it – playing baccarat with the villain in a casino, introducing himself as “Corbin … Michael Corbin,” and gallivanting around the countryside with a beautiful waif (Gabrielle Anwar in an early role) bent on revenge. All this time, his French class and their witch of a teacher get mistaken for a group of mercenaries and are kidnapped, then released, then kidnapped again, without ever realizing it.

Taken in context, If Looks Could Kill is a hysterically funny romp through the warped mind of a screenwriter intent on going way over the top. As such, the only time the film falters is when it slows down to needlessly develop the obligatory romantic subplot. Aside from some violence that borders on disturbing in the comedic way it’s played, there’s nothing even remotely serious about this film.

Predictably, If Looks Could Kill was hammered by most critics. But in a daring move, Roger Ebert gave it a “thumbs up” and said it “plays like a head-on collision between [James] Bond and Indiana Jones, if the primary goal of both of those heroes was transcendent silliness.” If Looks Could Kill gives us the best of all worlds: it’s a Bond spoof made with a big budget and written securely in contemporary comedic style.

Spy Hard (1996)

Whereas Our Man Flint had James Coburn trying to out-Bond James Bond, Spy Hard takes the opposite tack. Unfailing slickness is exchanged for utter stupidity as Leslie Neilson tries to out-Gump Forrest Gump.

Whereas Our Man Flint had James Coburn trying to out-Bond James Bond, Spy Hard takes the opposite tack. Unfailing slickness is exchanged for utter stupidity as Leslie Neilson tries to out-Gump Forrest Gump.

The film begins with an exceptional title sequence done in the Bond mold. Weird Al Yankovic sings the theme song – a head-on collision of Thunderball and GoldenEye – while silhouettes of naked women swim in the background. The women slowly get heavier and heavier and then morph into farm animals and furniture. Yankovic holds the final note so long his head explodes.

Neilson is Dick Steele, Agent WD40, and he’s assigned to foil the plans of General Rancor (Andy Griffith). He teams up with leggy Nicolette Sheridan in order to stop the launch of a deadly rocket. But, let’s face it, the plot is merely a framework to hang jokes and sight gags on. We’re treated to dialogue like: “Sir! We’ve just received an important message from our listening point on the Rock of Gibraltar!” – “Really? What is it?” – “Well, it’s a big rock on the Southern Coast of Spain.” Yuck, yuck.

The comedy style was done previously – and better – in such films as Airplane! And The Naked Gun. There’s the obligatory love scene with a lithe, beautiful women lying next to Neilson and his considerable belly, as well as cute gags like Alex Trebec as the voice on the self-destructing tape. Cameos abound, both from people who really need the work (Mr. T, Fabio, Roger Clinton) and people who should probably know better (Pat Morita, Dr. Joyce Brothers, Ray Charles).

Spy Hard's other mainstay is ripping off better movies. In addition to the central Bond rip-off, there are spoofs of Speed, Cliffhanger, In the Line of Fire, Jurassic Park, E.T., Sister Act, True Lies, etc. Bill Conti does the musical score (he also did For Your Eyes Only) and he somehow manages to snag a piece of every spy theme in history without getting himself sued.

Spy Hard's other mainstay is ripping off better movies. In addition to the central Bond rip-off, there are spoofs of Speed, Cliffhanger, In the Line of Fire, Jurassic Park, E.T., Sister Act, True Lies, etc. Bill Conti does the musical score (he also did For Your Eyes Only) and he somehow manages to snag a piece of every spy theme in history without getting himself sued.

Spy Hard is acceptable as long as it’s taken for what it is. The plot and characters are essentially replaced by low-brow humor and bathroom comedy. While not a good film by any stretch, it’s partially rescued by Neilson’s natural sense of comedic timing. It’s also helped by the fact that anyone who watches this kind of film invariably knows what he or she is getting and is probably in the mood for it.

Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997)

Yes, the unthinkable has happened. Bond spoofs have become so commonplace that they’ve begun to spoof themselves.

Yes, the unthinkable has happened. Bond spoofs have become so commonplace that they’ve begun to spoof themselves.

Mike Myers is both the title character – a super secret agent from the 60’s – and the nefarious Dr. Evil (who looks an awful lot like Donald Pleasance’s Blofeld from You Only Live Twice). The latter froze himself in an Earth-orbiting Bob’s Big Boy in order to come back 30 years later to try and take over the world. Powers got frozen as well, which sets the premise for the big joke of the film: What does a happenin’ hepcat from the swinging 60’s do in the uptight 90’s?

Bond film references abound. Dr. Evil’s henchman is a big Korean named Random Task who throws his shoe at people, prompting Powers to question, “A shoe? Who throws a shoe!?” Robert Wagner checks in as Number Two, whose mistress, Alotta Fagina (say it out loud), is one of Powers’s early conquests. Elizabeth Hurley, looking surprisingly Diana Rigg-ish, is the agent-in-training assigned to keep Austin’s mind in the job, though all he can do is tell her how much he wants to “shag.”

With Austin Powers, Myers is finally given a role where he can cut loose and do what he does best – namely, look ridiculous. His character is a mish-mash of 60’s cliches – Matt Helm-like sexual prowess, notoriously bad teeth, and an annoying penchant for aping campy 60’s lines like “It’s my happening, and I’m freaking out!” As Dr. Evil, Myers rolls together the most comic elements of the great spy film villains. At one point he threatens to put Austin in an “overly elaborate and easily escapable deathtrap.” The times, alas, have passed Dr. Evil by as well – he has unfortunately outdated plan to make it look like Prince Charles had an affair (gasp!) and blackmail the free world for “one million dollars!”

The film’s humor is a derisive look at all the silly things that make spy movies fun. At one point, all the villains give a round of maniacal laughter. But the camera doesn’t cut away like we’re used to – it simply holds the shot while the villains laugh again and again, until they slowly ebb away to an awkward silence with everyone looking at the walls and the floor. The bathroom humor gets overdone now and again, but most other laughs are belly-busters.

The film’s humor is a derisive look at all the silly things that make spy movies fun. At one point, all the villains give a round of maniacal laughter. But the camera doesn’t cut away like we’re used to – it simply holds the shot while the villains laugh again and again, until they slowly ebb away to an awkward silence with everyone looking at the walls and the floor. The bathroom humor gets overdone now and again, but most other laughs are belly-busters.

In the end, Austin Powers is a film carried solely on the back of its star. It’s hard to imagine an actor other than Mike Myers who could pull off something this mind-numbingly over-the-top. Once again, the broad strokes of the Bond films are securely in place, leaving the actors to make terrific fun of the certain British secret agent that made all this stuff popular. Myers and company do it with high style, thus ensuring Bond spoofs will survive into the next millennium.

Other Films

Dr Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine (1966): Beach Party regulars Frankie Avalon (as Agent 00 1/4) and Dwayne Hickman team up to quash the world-conquering schemes of Vincent Price’s malevolent Dr Goldfoot. Goldfoot has engineered an army of bikini-clad girl-bots (headed by the scrumptious Susan Hart) whom he plans to marry off to the world’s richest men. The claymation credits by Gumby creator Art Clokey and bouncy theme song from The Supremes help get this one off on the right (gold) foot. Originally conceived as a musical (a la the Beach Party movies), the nervous producers cut all the songs prior to the film’s release. A special edition of Shindig, titled: The Wild Weird World of Dr. Goldfoot, featured the missing musical numbers.

Dr Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine (1966): Beach Party regulars Frankie Avalon (as Agent 00 1/4) and Dwayne Hickman team up to quash the world-conquering schemes of Vincent Price’s malevolent Dr Goldfoot. Goldfoot has engineered an army of bikini-clad girl-bots (headed by the scrumptious Susan Hart) whom he plans to marry off to the world’s richest men. The claymation credits by Gumby creator Art Clokey and bouncy theme song from The Supremes help get this one off on the right (gold) foot. Originally conceived as a musical (a la the Beach Party movies), the nervous producers cut all the songs prior to the film’s release. A special edition of Shindig, titled: The Wild Weird World of Dr. Goldfoot, featured the missing musical numbers.Dr Goldfoot and The Girl Bombs (1966): This time Goldfoot’s girl-bots come equipped with “thermonuclear navels” with which to wipe out the Generals of NATO. Fabian is on the case, assisted by the Italian comedy team of Franco and Ciccio. Unlike its spirited predecessor, this one is just about as bad as it sounds. Mario Bava, Italy’s premiere fantasy director, manages to pull off a couple of visually delightful moments, but mostly it hurts to watch.

Out Of Sight (1966): A secret agent’s Walter Mitty-ish butler is mistaken for the real article, and finds himself battling to save a rock & roll concert from a pop music-hating villain. Despite appearances by a number of top singing groups of the day (The Turtles, The Animals, Gary Lewis and The Playboys), the film’s real highlight is a super-charged drag-racing spy car designed by George Barris, the man who created TV’s bitchin’ Batmobile! Warning!!! Screenplay by Larry (Hogan’s Heroes) Hovis!

Kiss The Girls and Make Them Die (1966): Spectacular scenery, gorgeous women, impressive candy-colored sets, glorious cinematography – all in service of a script you wouldn’t wrap fish in. Mike (Mannix) Conners and Dorthy Provine are competing secret agents on the trail of Vittorio Gassman, a billionaire psychopath whose fears of sexual inadequacy drive him to wipe out the Earth’s population via a rare plant – native to the upper Amazon – which extinguishes the mating urge. Once his mission is complete, he’ll single-handedly repopulate the globe using his deep-frozen harem. The similarities to Moonraker (right down to it’s Rio setting) are too numerous to mention. A terrible film on practically all levels, yet it manages to go right to the heart of the sex-as-power issues inherent in all spy films.

The Last of The Secret Agents? (1966): Corrupt art dealer Theo Macuse has recovered the lost arms of the Venus Di Milo and plots to steal the rest of her in this labored, unfunny spoof. This was to be the first of a series of films Marty Allen and Steve Rossi, a Las Vegas comedy team touted by the studio as the new Martin and Lewis. The film came out, and their seven-year, fourteen-picture deal quietly evaporated. ‘Nuff said. Nancy Sinatra sings the title tune, a shotgun wedding of “These Boots Are Made For Walking” and Thunderball-style horns.

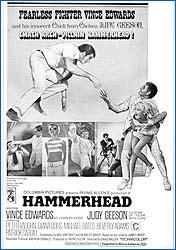

Hammerhead (1968): Rat-eyed Peter Vaugh plays Mr. Hammerhead, an oily villain who collects pornography because he appreciates its honesty. Vince Edwards is secret agent Mark Hood, a slow-witted slab of beef with no visible neck, and the hairiest arms this side of the San Diego Zoo. HammerheadBrit B-movie bird Judy Geeson does an irritating turn as a perky Chelsea girl who constantly gets under foot. The villain’s plot (stealing NATO documents with the aid of an imposter) is hopelessly routine. What sells the picture is its unerring sense of sleaziness, an atmosphere of stunted sexuality so unrelentingly puerile as to inspire glassy-eyed, slack-jawed astonishment. Producer Irving Allen, Beverley (Lovey Ktavzit) Adams and screenwriter Herbert Baker are among the Matt Helm alumni on board this sinking ship. David Wittaker’s score is pretty nice though.

Hammerhead (1968): Rat-eyed Peter Vaugh plays Mr. Hammerhead, an oily villain who collects pornography because he appreciates its honesty. Vince Edwards is secret agent Mark Hood, a slow-witted slab of beef with no visible neck, and the hairiest arms this side of the San Diego Zoo. HammerheadBrit B-movie bird Judy Geeson does an irritating turn as a perky Chelsea girl who constantly gets under foot. The villain’s plot (stealing NATO documents with the aid of an imposter) is hopelessly routine. What sells the picture is its unerring sense of sleaziness, an atmosphere of stunted sexuality so unrelentingly puerile as to inspire glassy-eyed, slack-jawed astonishment. Producer Irving Allen, Beverley (Lovey Ktavzit) Adams and screenwriter Herbert Baker are among the Matt Helm alumni on board this sinking ship. David Wittaker’s score is pretty nice though.Bonditis (1966): A nebbish obsessed with James Bond takes his analyst’s advice and heads to a remote Swiss village for rest and relaxation. Naturally, he falls right into a nest of international spies, all vying for a secret formula. The frantic opening sequence features animated lips and careening cartoon credits, over a full scale Bondian dream sequence.

Freddy as F.R.O.7 (1992): An international cast of stars, headed by Ben (Gandhi) Kingsley, lend their voices to this disturbingly irrational animated adventure. Freddy is an enchanted frog who evolves into a six-foot tall, talking, singing, sports car driving, cap and ascot-wearing secret agent for Her Majesty’s government. Along the way he meets the various mystical musical mutants, including the Loch Ness Monster. Freddy is the Eraserhead of big screen cartoons.

Freddy as F.R.O.7 (1992): An international cast of stars, headed by Ben (Gandhi) Kingsley, lend their voices to this disturbingly irrational animated adventure. Freddy is an enchanted frog who evolves into a six-foot tall, talking, singing, sports car driving, cap and ascot-wearing secret agent for Her Majesty’s government. Along the way he meets the various mystical musical mutants, including the Loch Ness Monster. Freddy is the Eraserhead of big screen cartoons.A Man Called Flintstone (1966): For the big screen debut of the popular TV cartoon, nothing less than a globe-hopping musical spy film would do. Fred turns out to be the perfect double for the recently injured secret agent Rock Slag. Soon Fred, Barney and their families are on an international chase to track down the evil Green Goose, and to smash his vile criminal organization, SMIRK. The Flintstones did it all better (and shorter) on TV with an episode featuring their spy hero, Jay Bondrock.

Condorman (1981): Disney just never “got” any of the big trends they themselves didn’t create. Evidence The Black Hole (a telling title if there ever was one), and this 10-years-too-late Bond spoof. Michael Crawford stars in this gadget-bloated staging of Robert Shecky’s whimsical novel, “The Game of X.” Crawford (affecting an irritating Midwest twang in the Dick Van Dyke role) is a comic strip artist mistaken by the Russians for a non-existent secret agent. When the Americans decide to use him on an actual mission, they provide him with the necessary cash to build working versions of his comic book hero’s fantastic arsenal. Barbara Carrera (two years away from her sexually charged spitfire role in Never Say Never Again) is a surprisingly lifeless femme. But Oliver Reed brings unexpected weight and dignity to his performance as a deadly Russian spymaster. The film opens with Crawford, decked out in his Condorman flying suit, making a leap off the Eiffel Tower – a stunt repeated four years later in A View to a Kill.

About The Authors

Michael Monahan lives in Berkeley, California. with his indulgent wife, Dee, and two pampered dobermans, Cody and Hobie. Mike was the musical leader of the 80s cult band Terminators of Endearment (ask him about “Ninja Hookers” sometime), and is one of those perverse admirers of the cinematic Casino Royale.

Deane Barker is a co-editor of MKKBB. He hates Casino Royale and all its perverse admirers.

Postscript

This is what the original article looked like when it was posted to MKKBB back in the 90s.